Abhinand Kishore

Abhinand Kishore

Archipelago of Margins: Caste, Class, Climate Change and the Urbanisation of Kochi

Archipelago of Margins: Caste, Class, Climate Change and the Urbanisation of Kochi

Archipelago of Margins: Caste, Class, Climate Change and the Urbanisation of Kochi

Abhinand Kishore

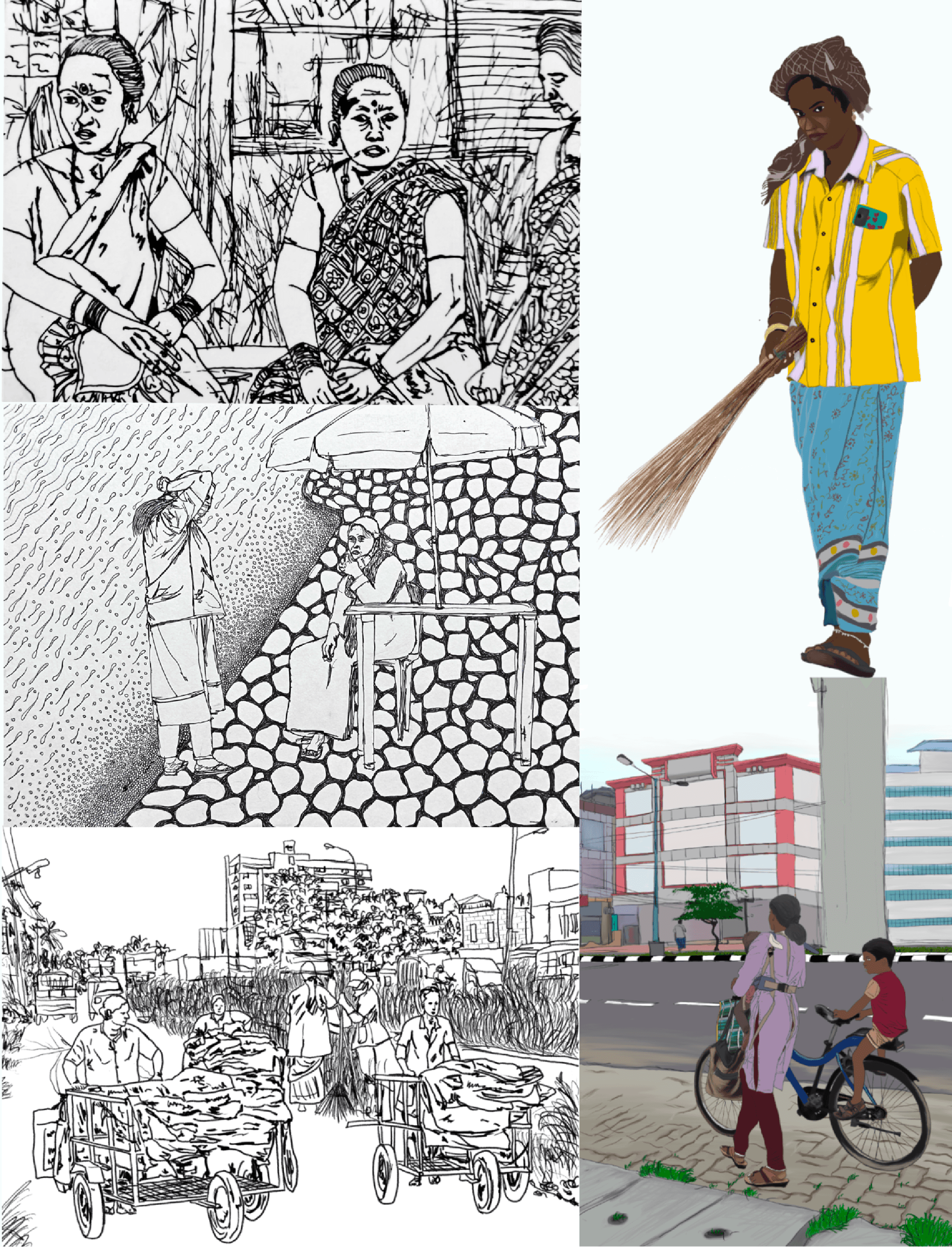

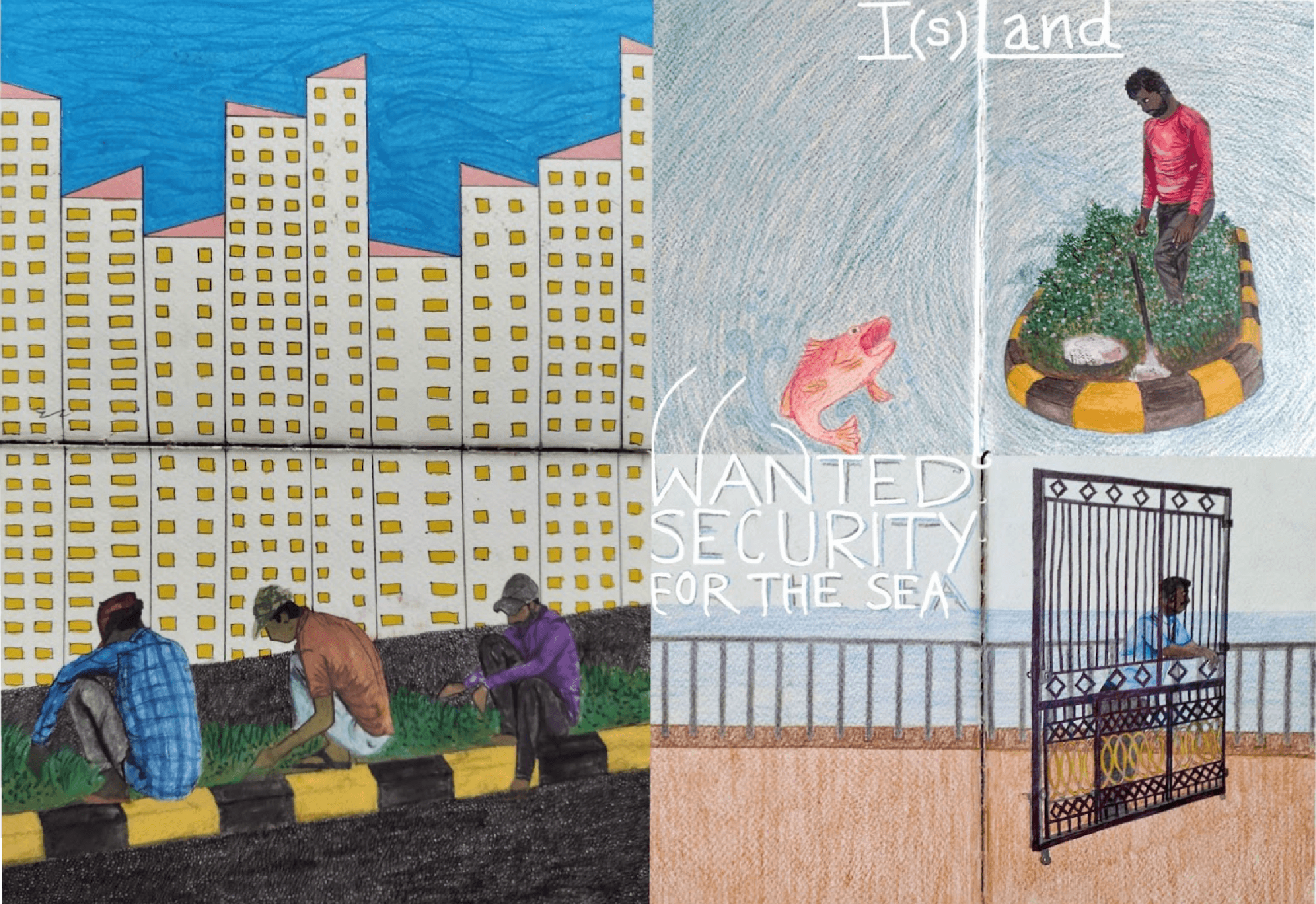

Images by Abhinand Kishore

Images by Abhinand Kishore

Abhinand is a visual artist and researcher with a multidisciplinary background, seeking to integrate ethnographic inquiry, creative expression, and community- and ecology-oriented practice into his everyday life. Currently pursuing PhD at MG University Kottayam, studying the urbanisation of Kochi, with focus on housing inequity, regimes of dispossession and socio-ecology.

Abhinand is a visual artist and researcher with a multidisciplinary background, seeking to integrate ethnographic inquiry, creative expression, and community- and ecology-oriented practice into his everyday life. Currently pursuing PhD at MG University Kottayam, studying the urbanisation of Kochi, with focus on housing inequity, regimes of dispossession and socio-ecology.

Abhinand is a visual artist and researcher with a multidisciplinary background, seeking to integrate ethnographic inquiry, creative expression, and community- and ecology-oriented practice into his everyday life. Currently pursuing PhD at MG University Kottayam, studying the urbanisation of Kochi, with focus on housing inequity, regimes of dispossession and socio-ecology.

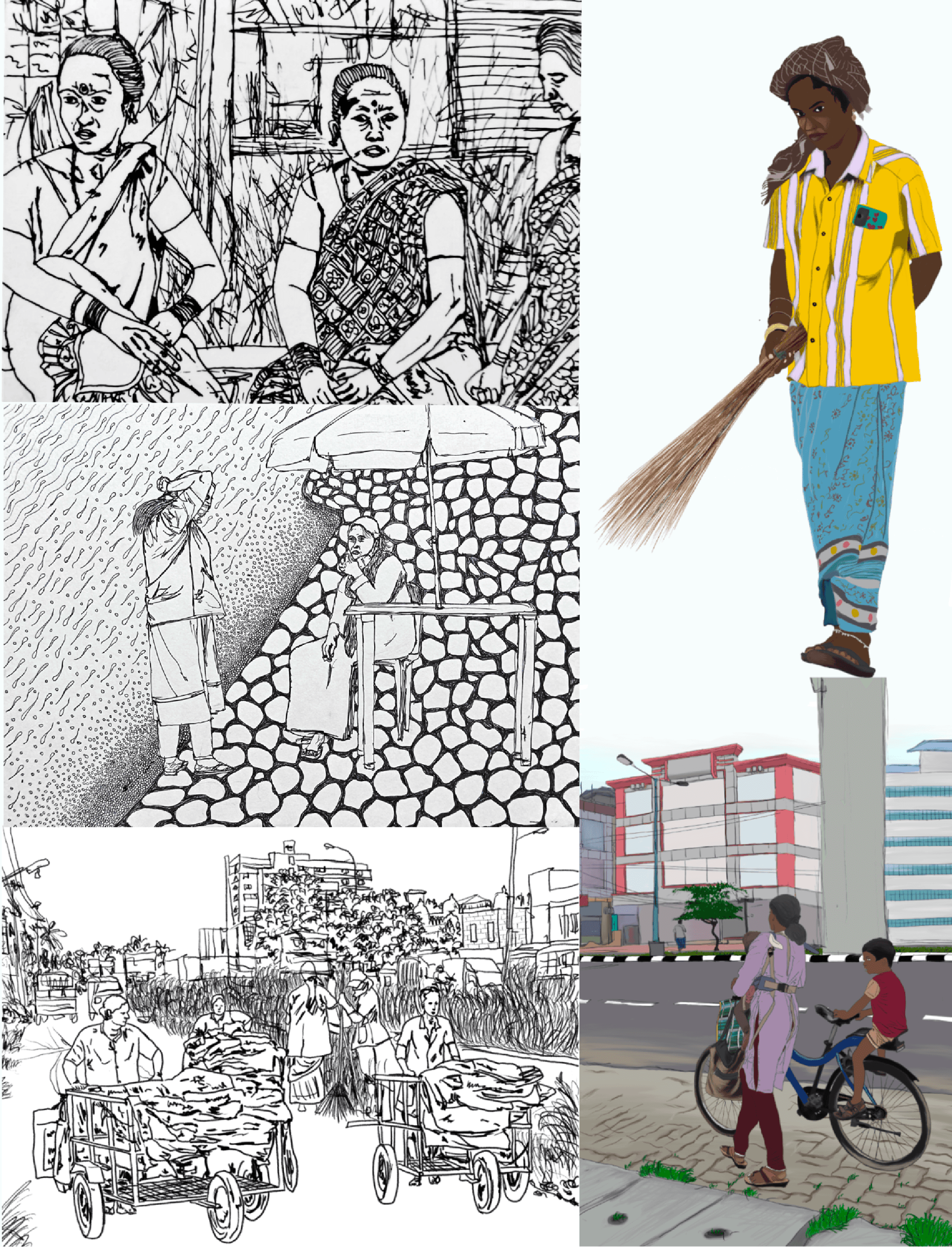

Kochi does not reveal itself as a whole, but in fragments—an archipelago of margins where land, water, labour and capital meet. This visual essay is an attempt to piece together an understanding of Kochi’s urban transformation from an edge perspective. It is born from my PhD studying the urbanisation of Kochi.

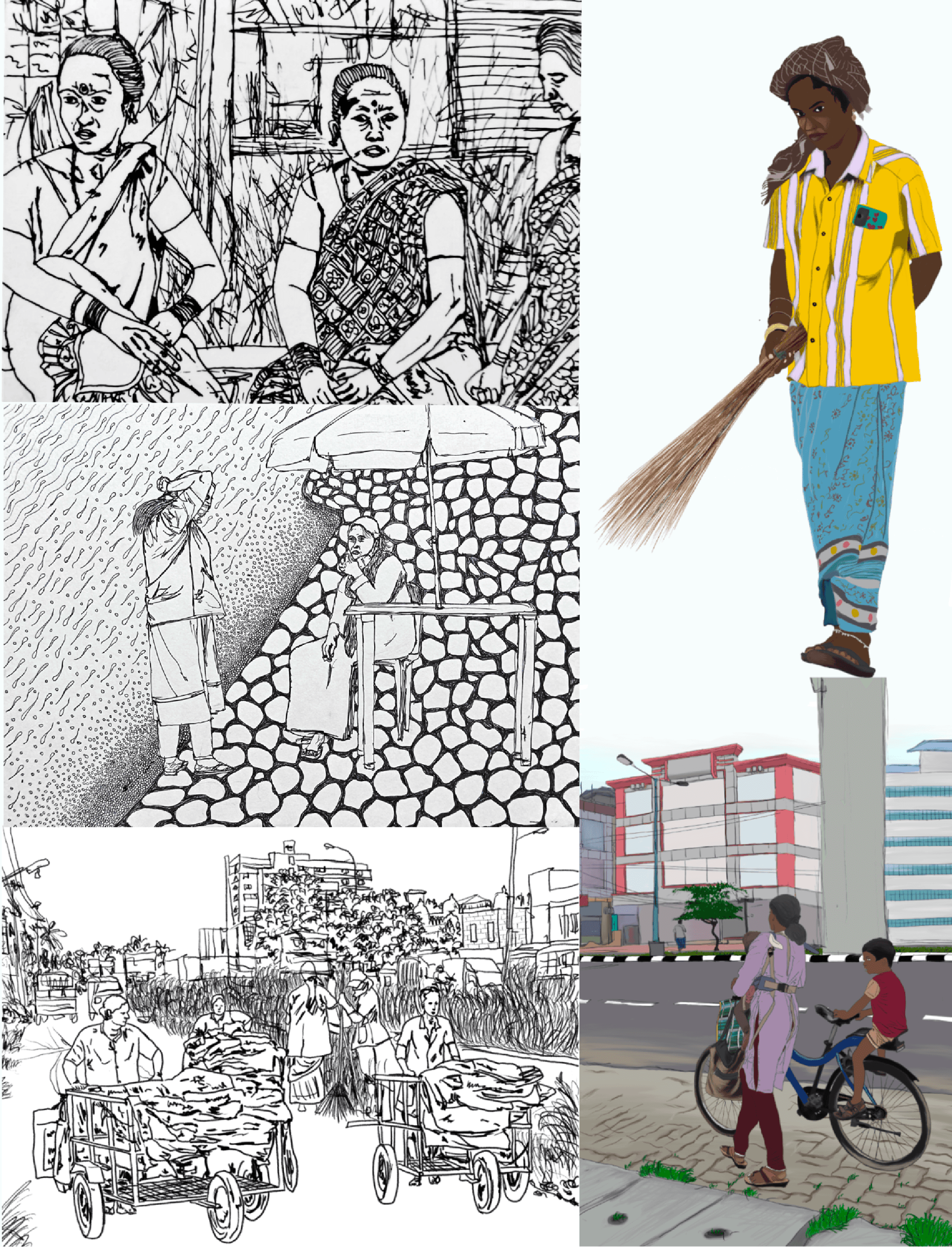

When I began ethnography, I was in an exploratory mode, thrown into the field with all senses wide open. I walked alone and with others, and cycled to the junctions and edges, across the nook and corner of Kochi. Sometimes I took the bus, auto, metro and boat to experience other nodes of ‘in-between places’. Drawings and photography went parallel to writing. A visual narrative emerged as a dialogue between images and text with my flows across the shores of Arabian sea, Vembanad lake, rivers, canals, wetlands, rail and highways. Unintended, but organic!

The history of Kochi, from its origin as a natural harbor to its transformation into an engineered port city, reflects a complex interplay of geography, trade, migration, hybrid cultures, colonialism, technology, labour and capital. Ultimately, the evolution of Kochi is entwined with the flow of water, people, labour and capital. Kochi’s layered histories of settlement by Jews, Hindus, Christians and Muslims of different places of origin, caste, class and language have given rise to a diverse urban landscape often hailed as an abode of cosmopolitanism. Yet, beneath this romanticized narrative lies a more complex urban fabric, where coexistence is fragmented by gentrification and ghettoisation.

Unlike the centralized density of the mega cities of India, Kochi’s margins are dispersed across its coast, canals, islands, wetlands, and transport nodes, making marginalisation not just peripheral but archipelagic. These ‘rurban’ margins—where rural livelihoods, urban expansion, ecological vulnerability, and infrastructural neglect coalesce—are neither fully urban nor fully rural. They are marked by hybrid rhythms: rising sea level, tidal cycles, seasonal labour, partial infrastructure/service access, and intermittent governance. Kochi’s marginality is thus shaped by a distinctive coastal urban metabolism, where land, labour, capital and water converge to constantly reconfigure the conditions of survival.

Art is integral to sense-making; it doesn't just complement text, but invites different thinking. It becomes a critique—not just of urban form, but of urban knowledge itself. It becomes a method, a way of knowing, sensing, and thinking with the city, and of composing knowledge that is affective and grounded. This method reflects a politics of feeling, of sensing. It challenges the textual and technocratic dominance in knowledge-making and asserts the validity of felt experience as knowledge. More importantly, crafting consensus and solidarity requires more than just political will; it needs creative engagement that evokes the emotions, memories, hopes and dreams of citizens of the city.

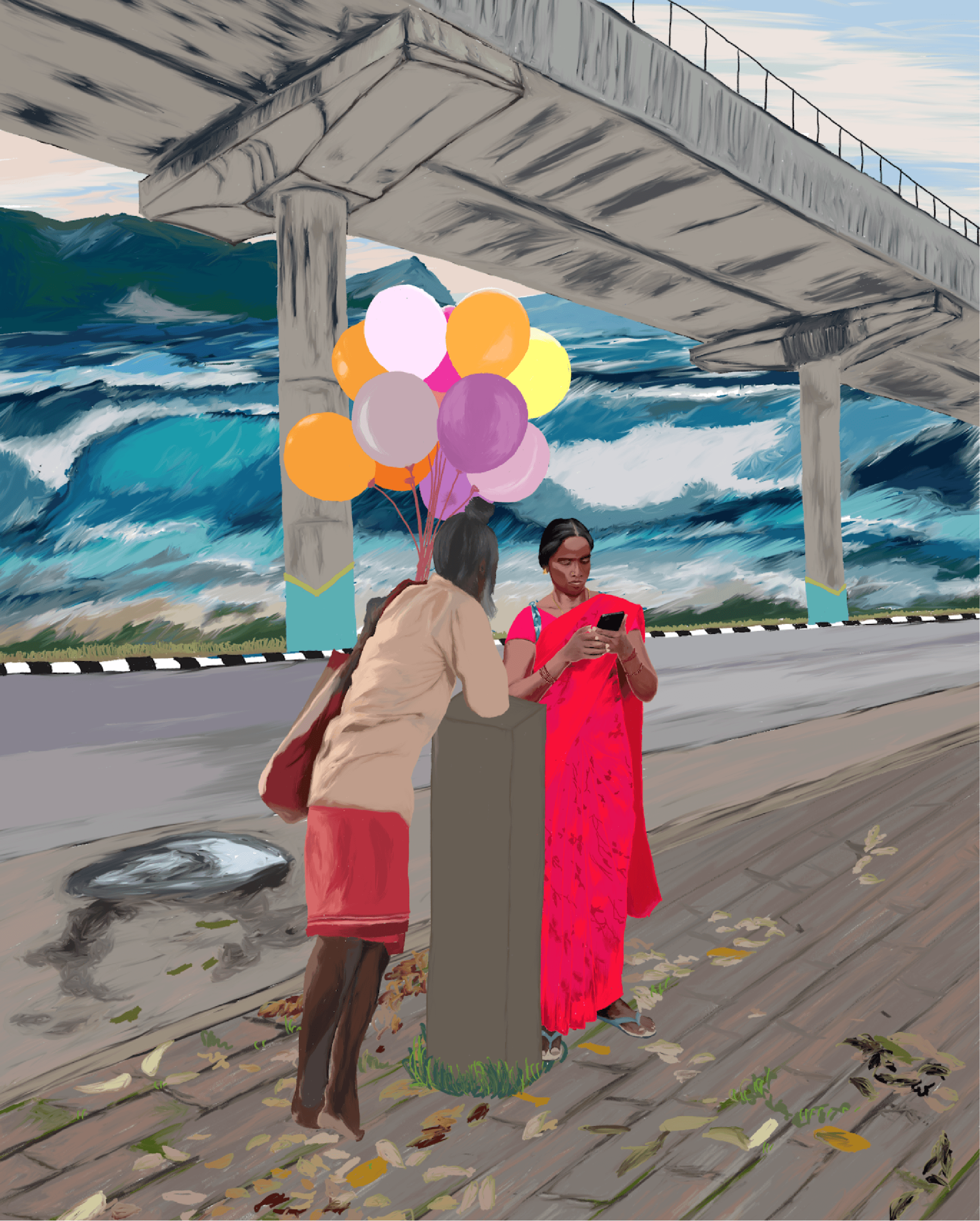

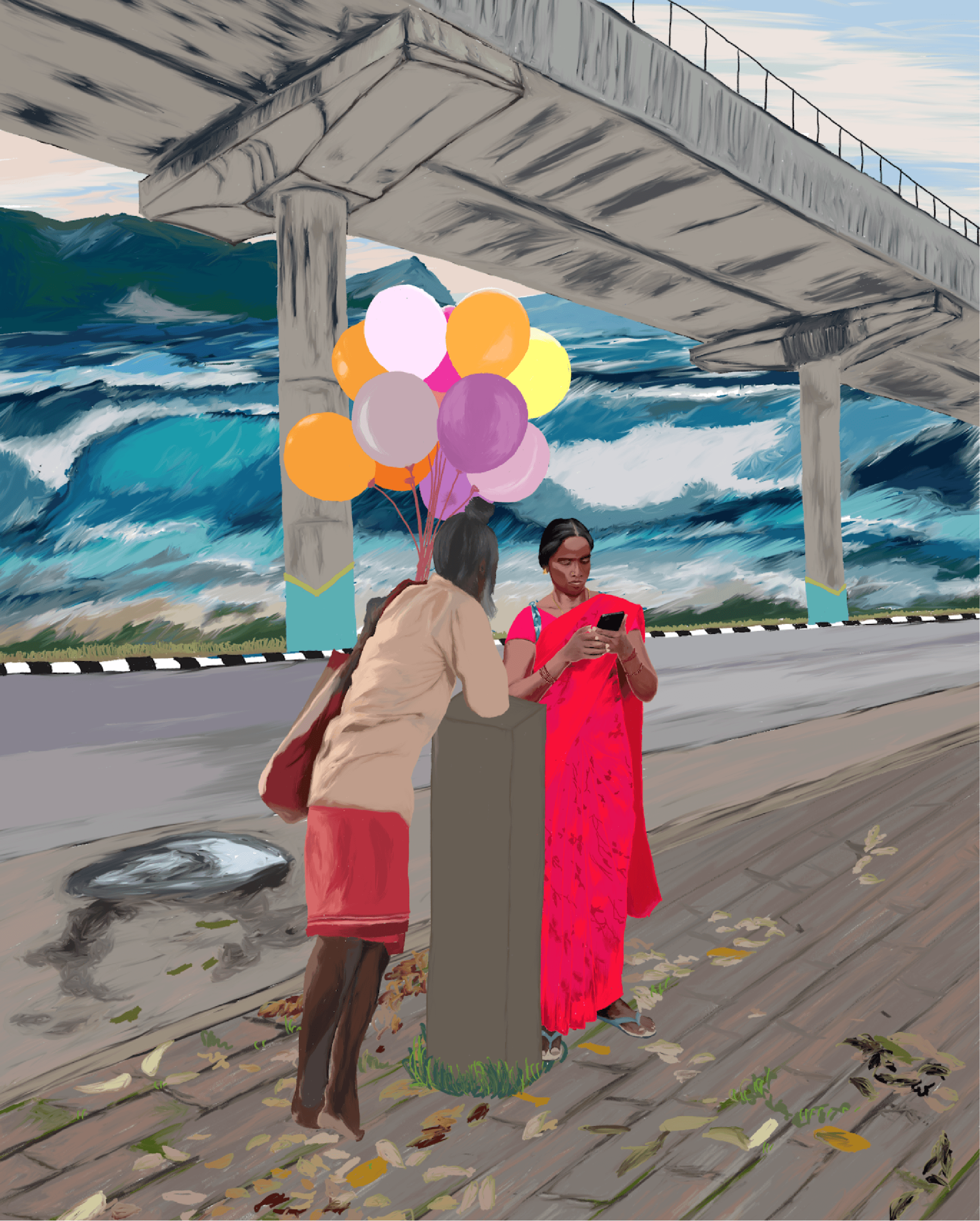

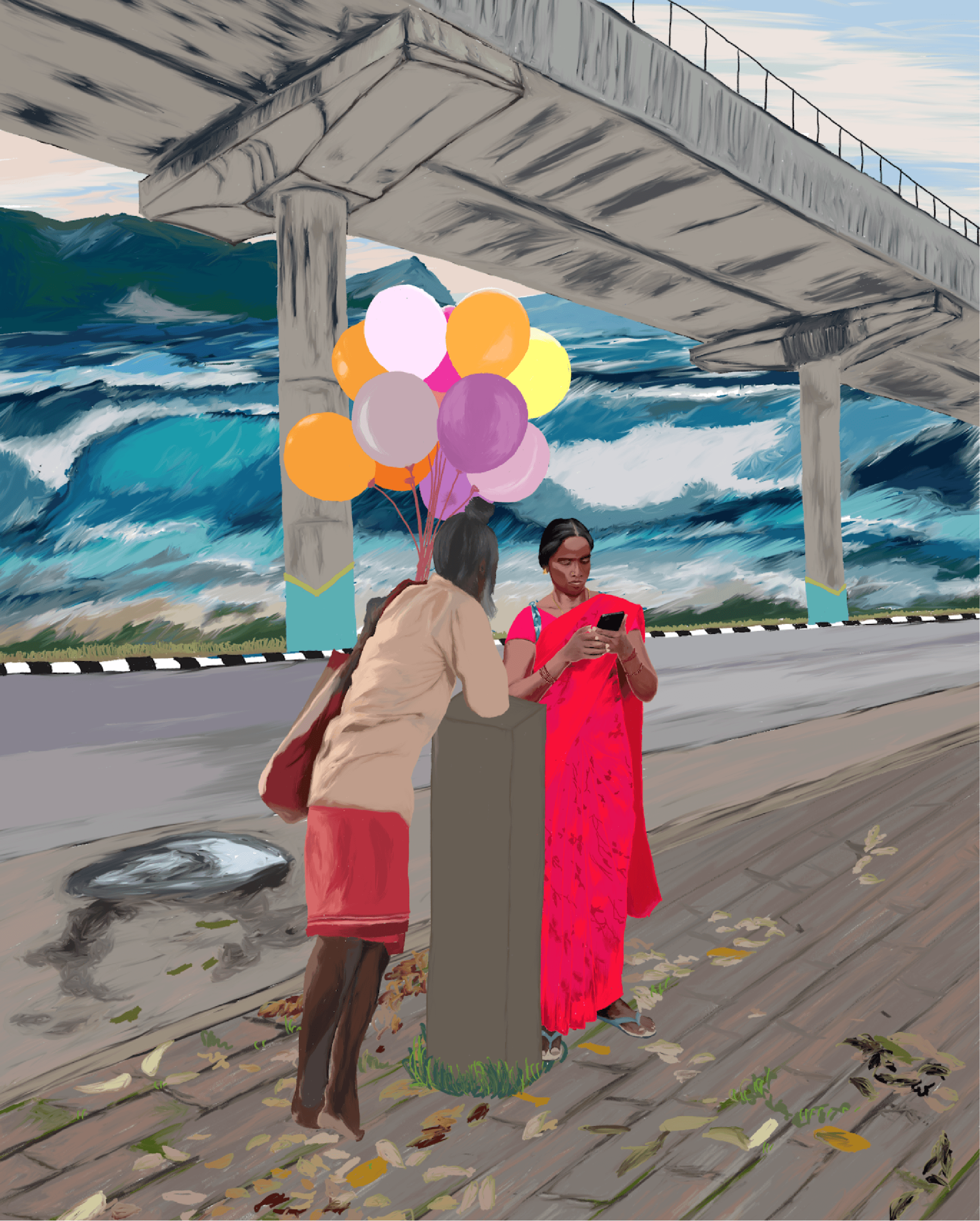

Them: Love & Care amidst precarity and chaos of survival. Beside the Salem-Kochi highway, near Edappally, one a balloon seller, familiar presence near Ernakulathappan Ground and the other, a construction worker I once noticed resting at a bus shelter in Vathuruthy. The metro—a symbol of mobility and modernity—contrasts with the ocean, restless and unpredictable, revealing the coastal fragility beneath Kochi’s development narrative.

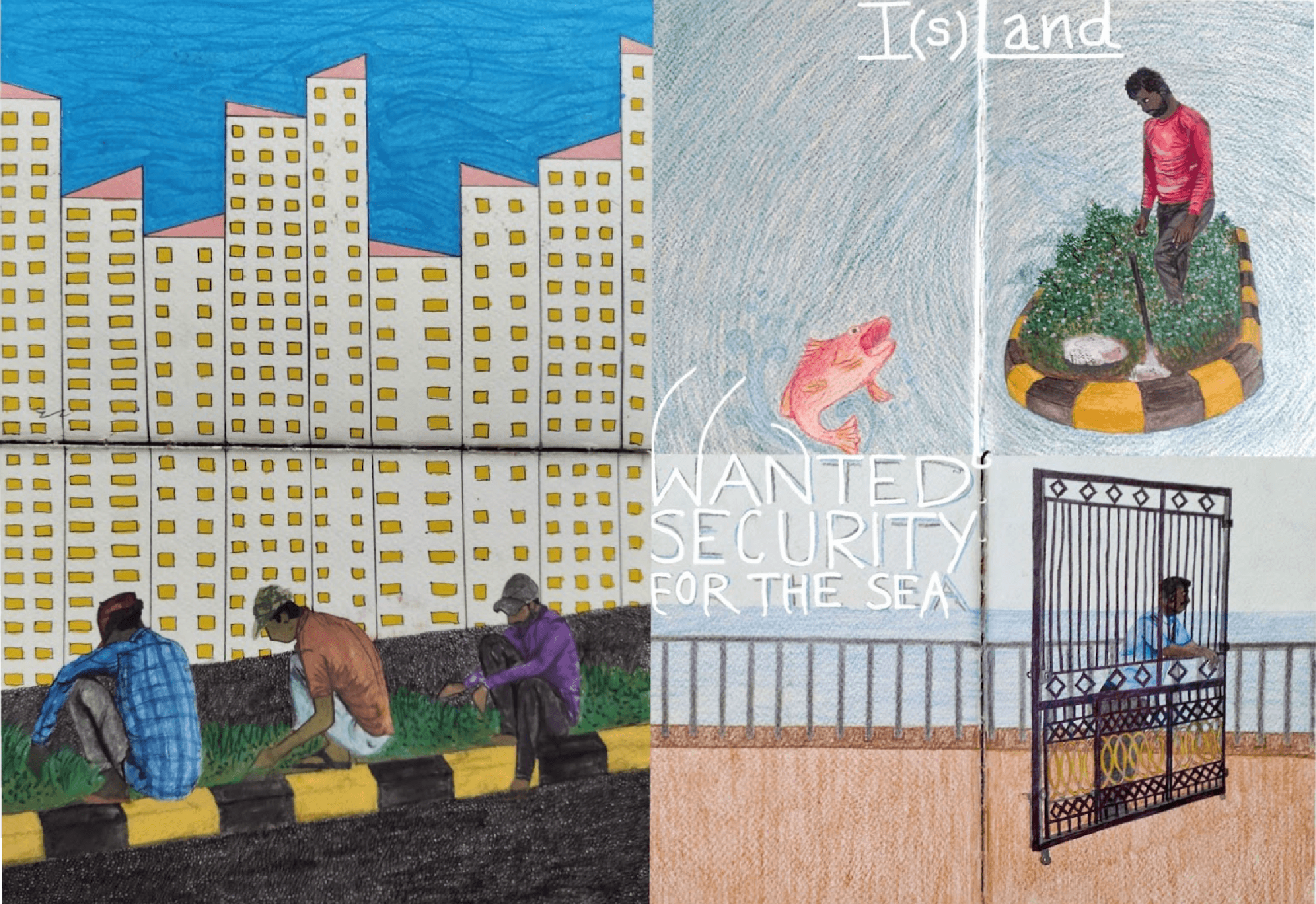

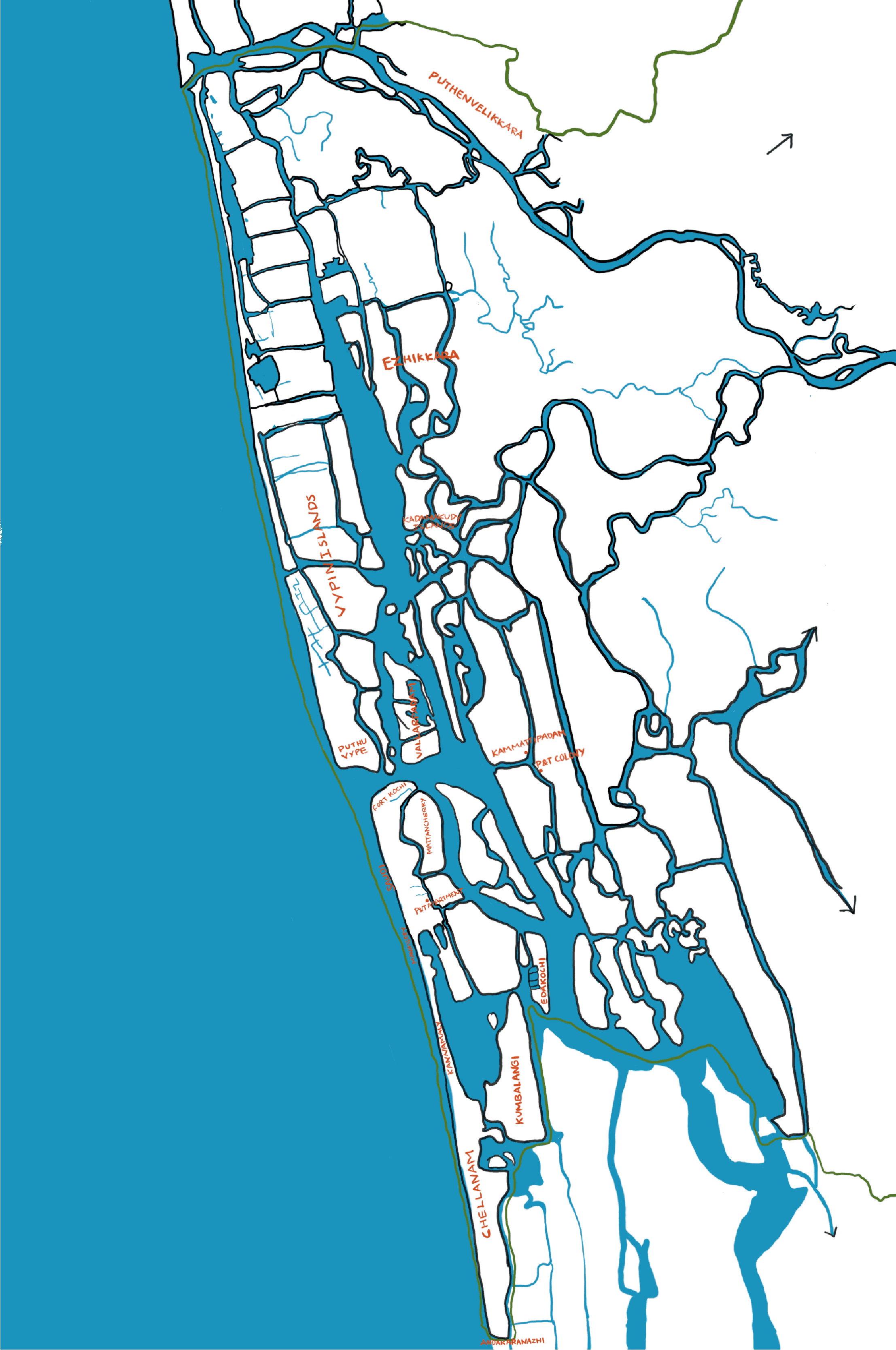

We will move through specific places in Kochi: P&T colony/apartment, Kammattipadam, Chellanam, Edakochi and the wider coastal belt—places that form interconnected nodes of archipelagic margins. This archipelago lives on the entangled forces of caste, class, religion, climate change, and urbanisation, where marginality unfolds in three entangled forms: social, spatial and sensorial.

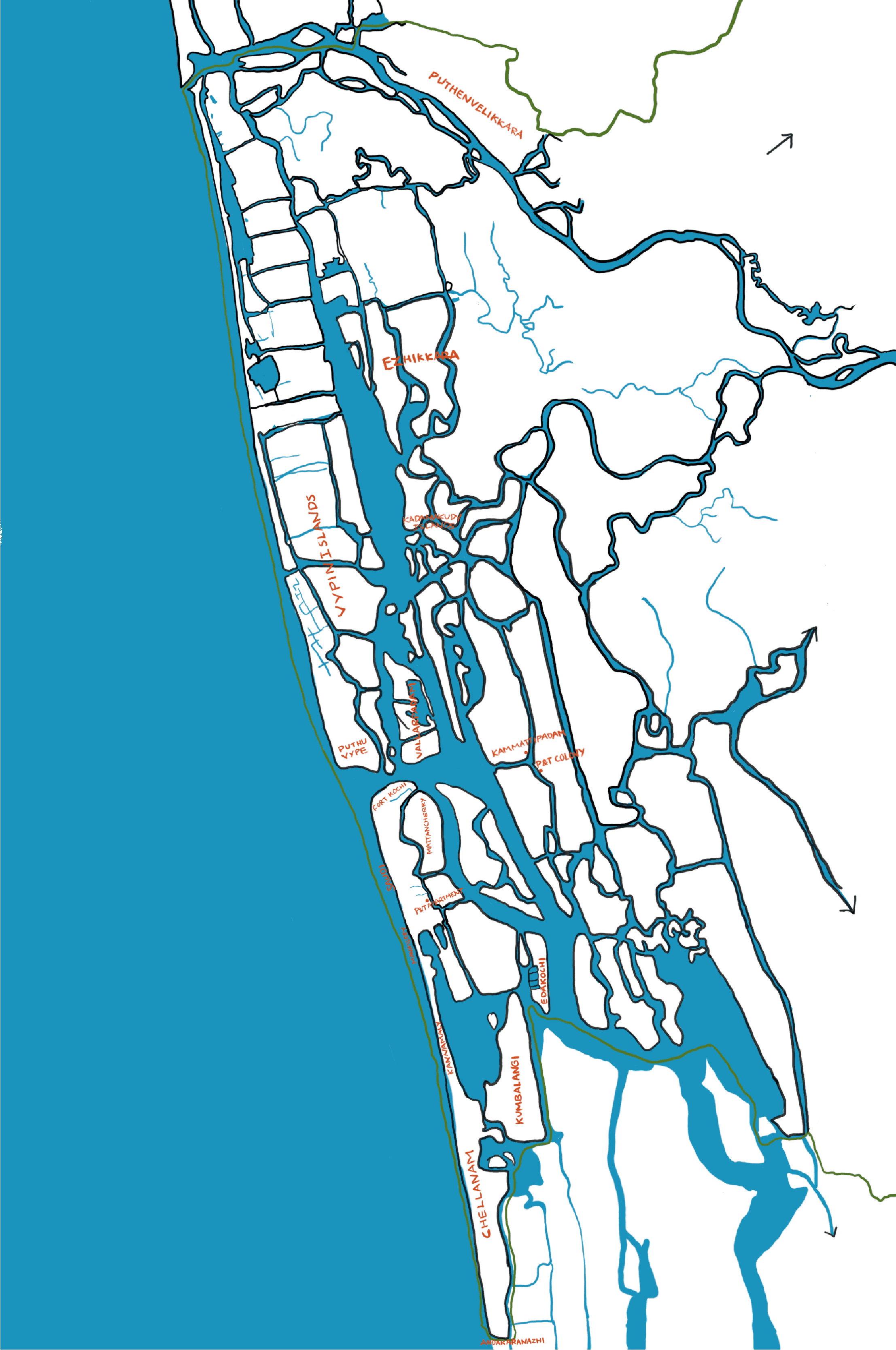

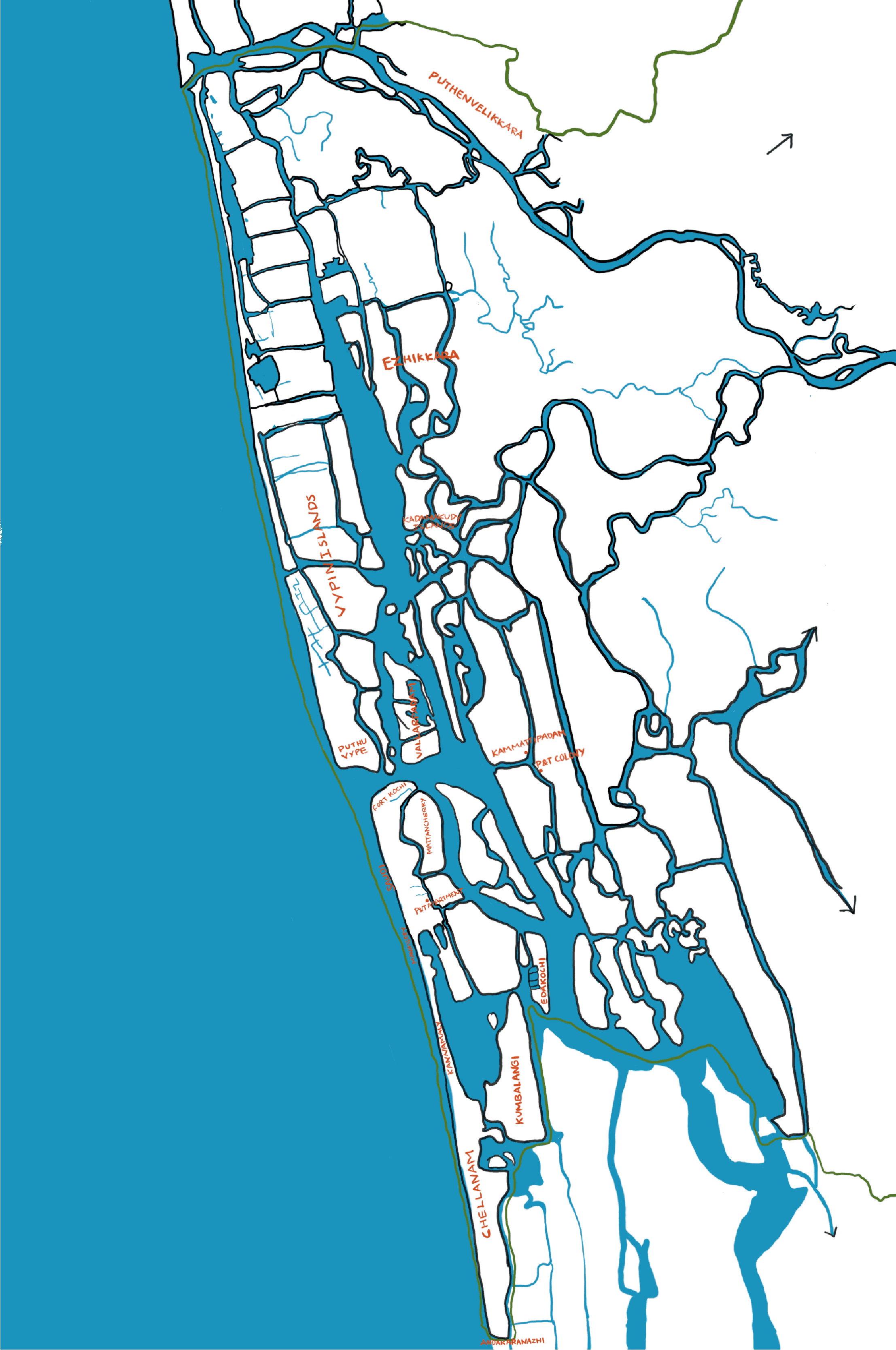

Kochi city region

From P&T Colony to P&T Apartment: From Flood to Leak

“There we feared the water rising above our feet, now we fear the water from above,” Mini, a Dalit domestic worker and a resident of P&T apartment said with anger and anguish, about how their rehabilitation from colony to apartment turned into another cycle of disregard and neglect. Their old fear was the water below, the Perandoor canal relentlessly rising with tidal or rain water flood. Their new fear is the water from above, dripping through cracked ceilings and leaking toilets in the apartment that was meant to be their salvation.

P&T Colony – before and after demolition

Their story begins in the 1970s on Poramboke land on the shore of the Perandoor canal, behind the Ernakulam south railway station. Pushed to the margins of the city by debt, familial betrayal, and poverty, 80 families—Dalits, Ezhavas, a few Nairs and others—forged a community united by dispossession. Most of the women worked as domestics, men in precarious jobs. Despite its mixed caste composition, the label ‘colony’ branded all residents as Colonikkar—outcasts— morally distant and socially inferior.

Inside the P&T colony

Smitha, who lived in the colony till she married and moved away, remembers her childhood with a sense of shame. She describes being drenched in sweat at school after helping her mother with domestic work and the devastating moment a school friend cut her off because the friend’s father found out where she lived. Even Nair residents like Jagathamma lost nominal caste privilege, desperately insisting “I'm a Nair, dear”, as offered food was declined. A place like ‘colony’ becomes a caste-marker in itself, overriding other identities. Where you live determines who others believe you to be.

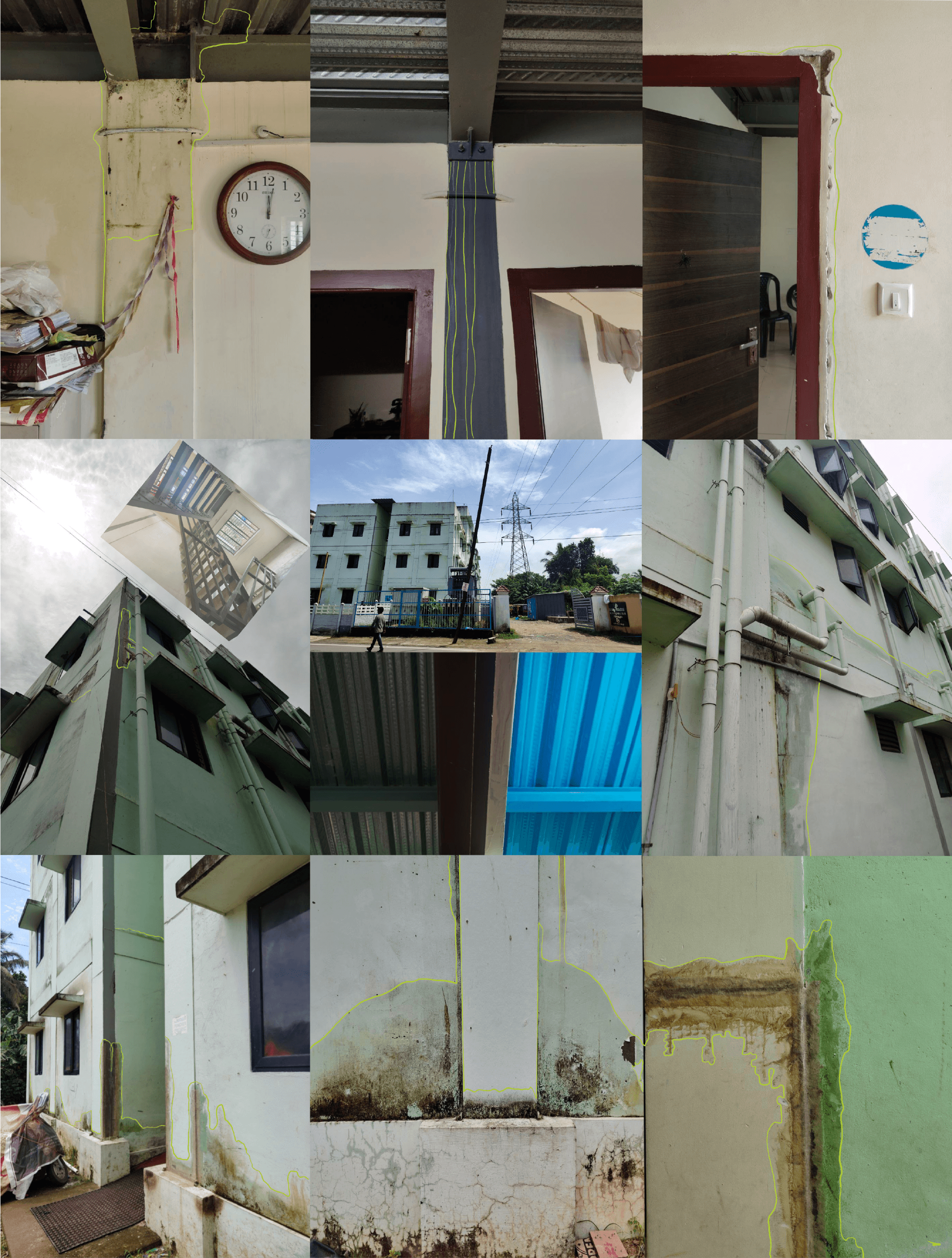

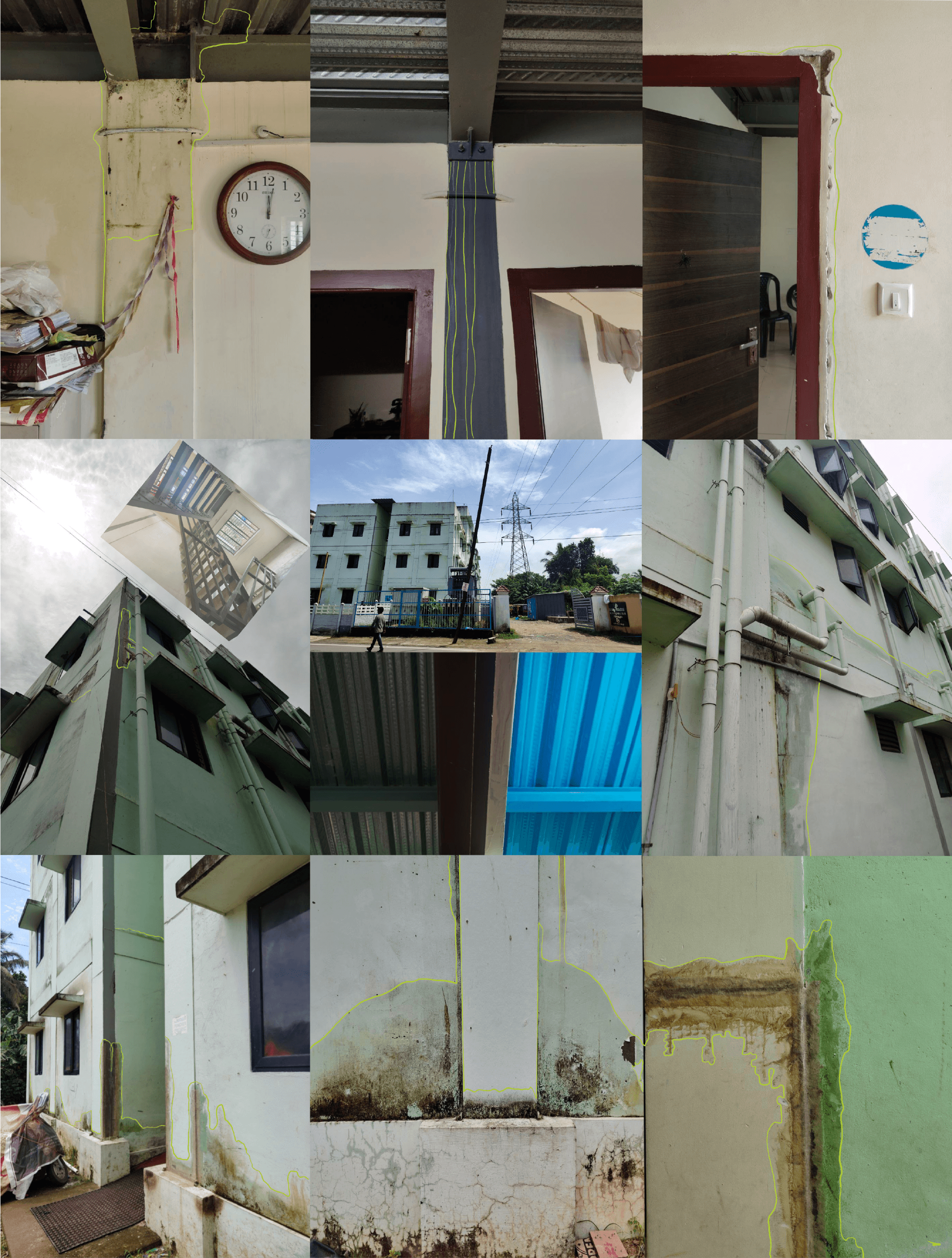

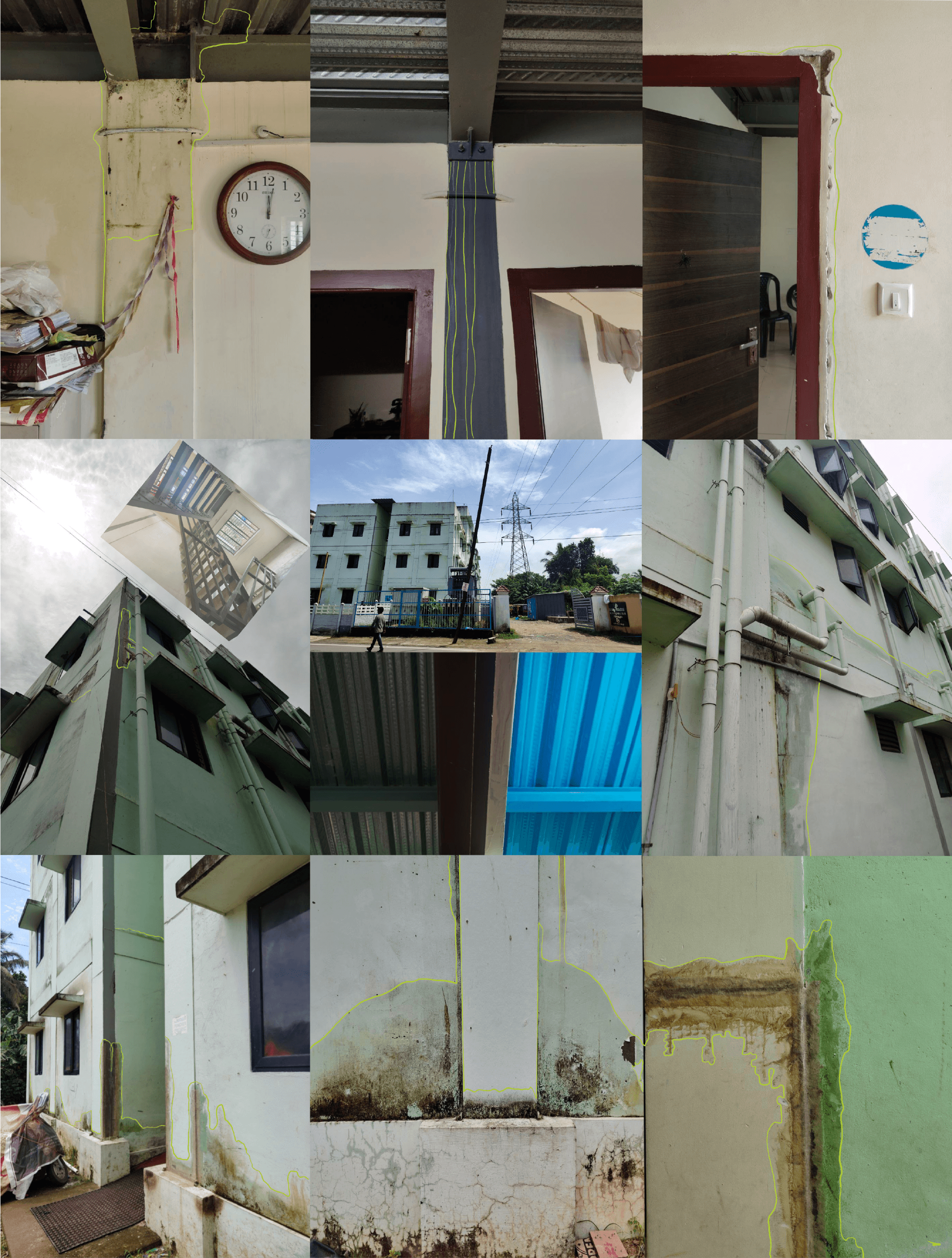

P&T Apartment: Leaks & Cracks

Life in the colony was an everyday battle against tidal or rainwater floods, infectious diseases, and the stench of the canal. Their rehabilitation to the new LIFE Mission-GCDA apartment, on January 26, 2024, was supposed to be the end to this undignified life. Instead, it brought new burdens: leaking roofs and toilets, cracked walls, a multi-story building without a lift, and disrupted access to city-centre jobs. The colony’s formation and stigmatization demonstrates how caste and class inseparably co-constitute urban marginality. People’s lives are subjects of state “experimentation”, devoid of agency and care.

P&T Colony & Kammattipadam along Perandoor canal

Kammattipadam: Rail-locked Pit of Flooded Ernakulam

Flooded KSRTC stand

Nestled behind the KSRTC stand, encircled by affluent neighbourhoods, near the Perandoor canal, lies the rail-locked Kammattipadam – a name derived from ‘kammatti’ grass that once thrived in its now concrete-filled paddy fields. Once fertile, the Pulaya (Dalit) and Kudumbi farmlands, which are now reduced to a triangular pit surrounded by rail, drown frequently in tidal and rain water. Aravindakshan, a resident of Kammattipadam, recalls childhood harvests with his grandmother, the landscape sustained by the life-giving Perandoor canal. This changed when the urban planners filled the paddy fields, destroying the existing drainage. The Kottayam-Ernakulam railway line severed the landscape, trapping tidal and rain water, neglecting drainage systems. “Every year,” Aravindakshan says “the railway increases its height, and we sink lower.”

Where is the water way?

Encroachment by both private and government entities, reckless dumping of plastic and construction waste, and the paving over of waterways to create roads and makeshift markets have drastically reduced the capacity of Kochi’s intricate network of canals. The Perandoor canal narrowed from 13m to 3m over 6km, becoming a stagnant polluted ditch.

Ditch: Between KSRTC stand & Rail

Today, 45 families—predominantly Dalits, with some Christian and Tamil migrants—live here. Electricity arrived only in 1991 via SC funds after relentless struggle. Trains blocking the sole access for more than one hour endanger lives during medical emergencies.

A Tamil migrant peanut seller living in Kammattipadam

“If Nairs and Namboodiris lived here, this problem would be solved in minutes,” says Aravindakshan. The caste dimension of neglect is inescapable; Dalit communities lack the political leverage and social capital to force action. Once a communist stronghold, years of party indifference have fractured community solidarity, pushing some towards Congress and the BJP in desperate search of justice and recognition.

Kammattipadam

The Paradox of the Kerala Model

There is no doubt that the modern Malayali identity—shaped by global trade, cross-cultural relations, socio-religious reforms, colonial administration, communist movements and the social democracy model—is putatively superior to that of other Indian states. Yet, beneath this narrative of progress lie deep-rooted hierarchies along the entangled lines of caste, class, religion, gender and region, that are further exacerbated and exposed by climate change and rapid urbanisation.

The 2018 floods uncovered the disproportionate impact on the marginalized: their losses, compounded by historical vulnerability and scarce resources, created wounds far deeper than those suffered by people who possessed the means to recover and rebuild their livelihoods. This inequality is built upon a foundation of incomplete social reforms.

Lottery, Liquor, Ration: Relief? A street dweller, a lottery seller at a flood relief camp, and a man outside a bar. For the marginalized, “relief” is too often reduced to charity, ration kits, or welfare handouts. Long standing demands—land redistribution for Dalits, autonomy for Adivasi communities, dignity in housing and labour—remain ignored. Even under a communist government, systemic justice gives way to token relief.

While the land reforms¹ of the 1970s addressed, even if partially, the class aspect of land question, it failed to address its caste and community aspects. The landless agricultural labourers, Dalits and Adivasis were relegated to flood-prone lands, colonies (3/5/10 cent plots) and remote, landslide/wildlife attack-prone highlands². Meanwhile, the corporates, dominant castes and elites continue to control the fertile garden land, wetland rice tracts and the plantations, with Adivasis and Dalits continuing to lose land through mortgage and fraud.

Tea over the hills: The Pettimudi landslide in the Western Ghats, Idukki, of 2020, destroyed 2 Layams (plantation workers colony) killing 66 people.

Centuries of caste-feudal domination and post-independent land reforms have entrenched the marginalisation of oppressed communities, while post-liberalisation policies like the SARFAESI Act and SEZ rules have accelerated land dispossession. Dalits and underprivileged OBC groups (including Latin Christians, Muslims, Dheevaras, and other Hindu communities) have been pushed into ecologically fragile and economically vulnerable zones. This pattern is starkly visible in coastal regions, where large-scale projects like the Cochin Port development and Vallarpadam Container Terminal have disrupted the traditional fishing and farming economies and undermined the very survival of coastal residents. In Kochi, areas such as Chellanam, Edakochi, Kumbalangi, Vypin, Ezhikkara and Puthenvelikkara stand on the frontline of vanishing land amidst unjust urbanization and intensifying climate change.

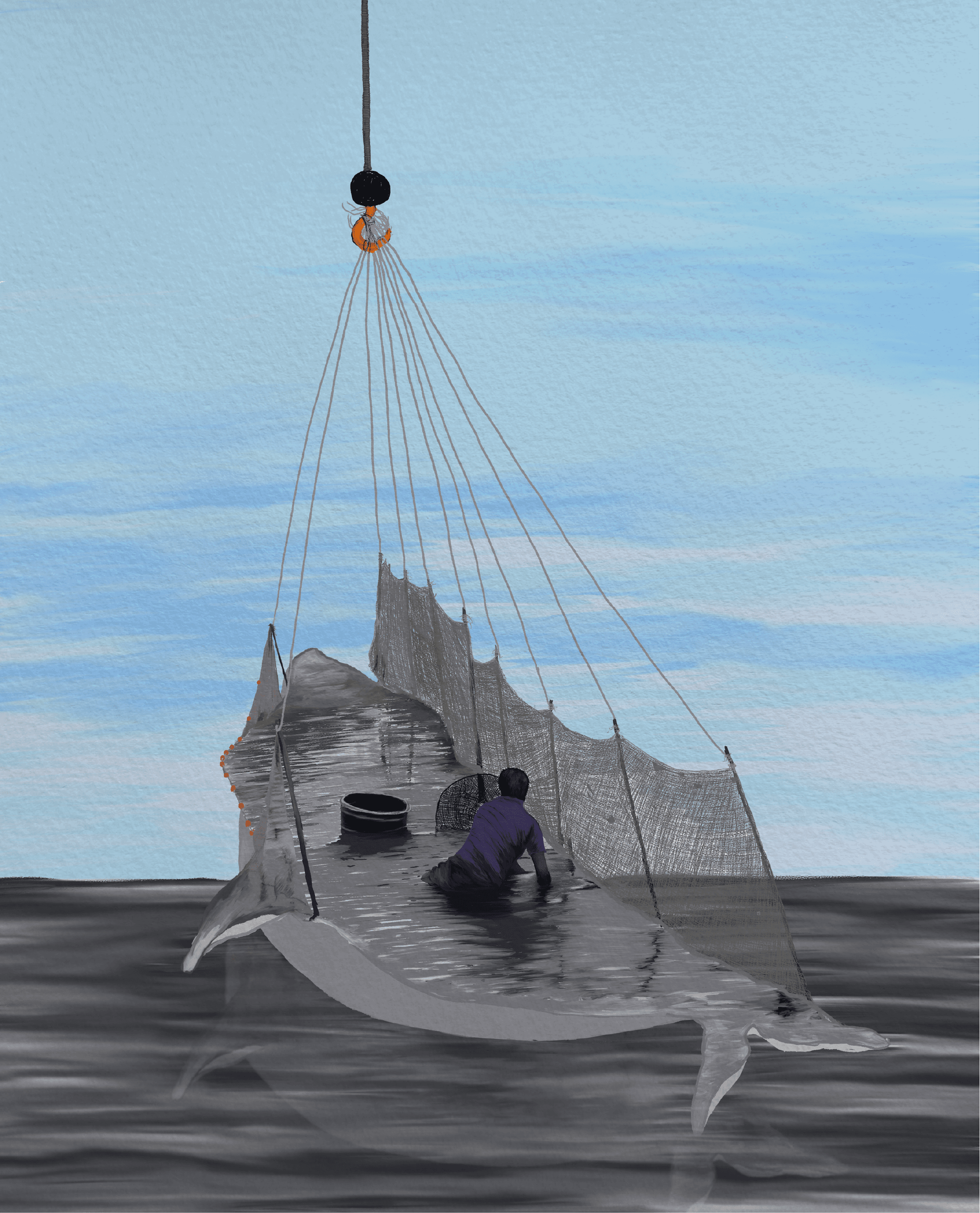

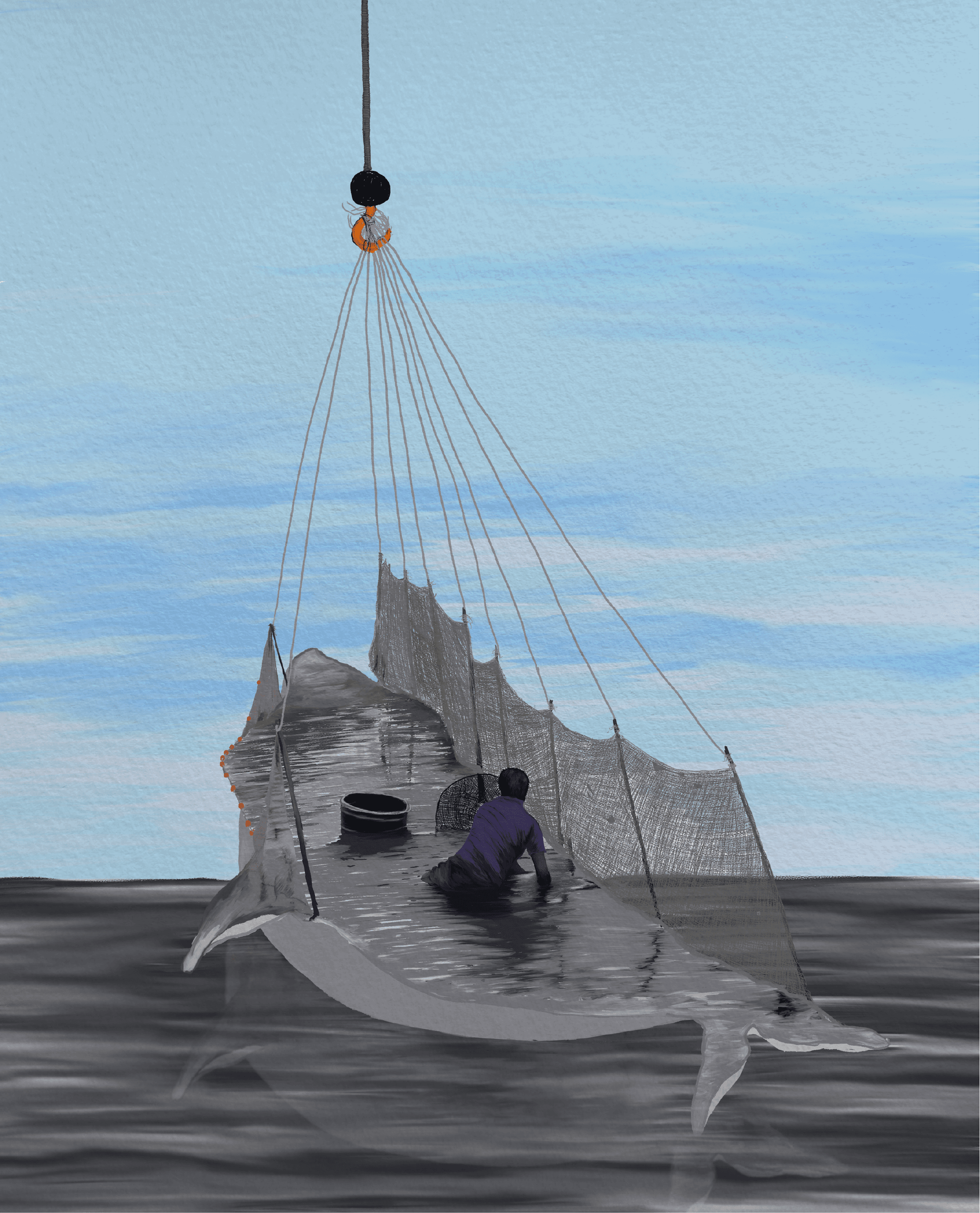

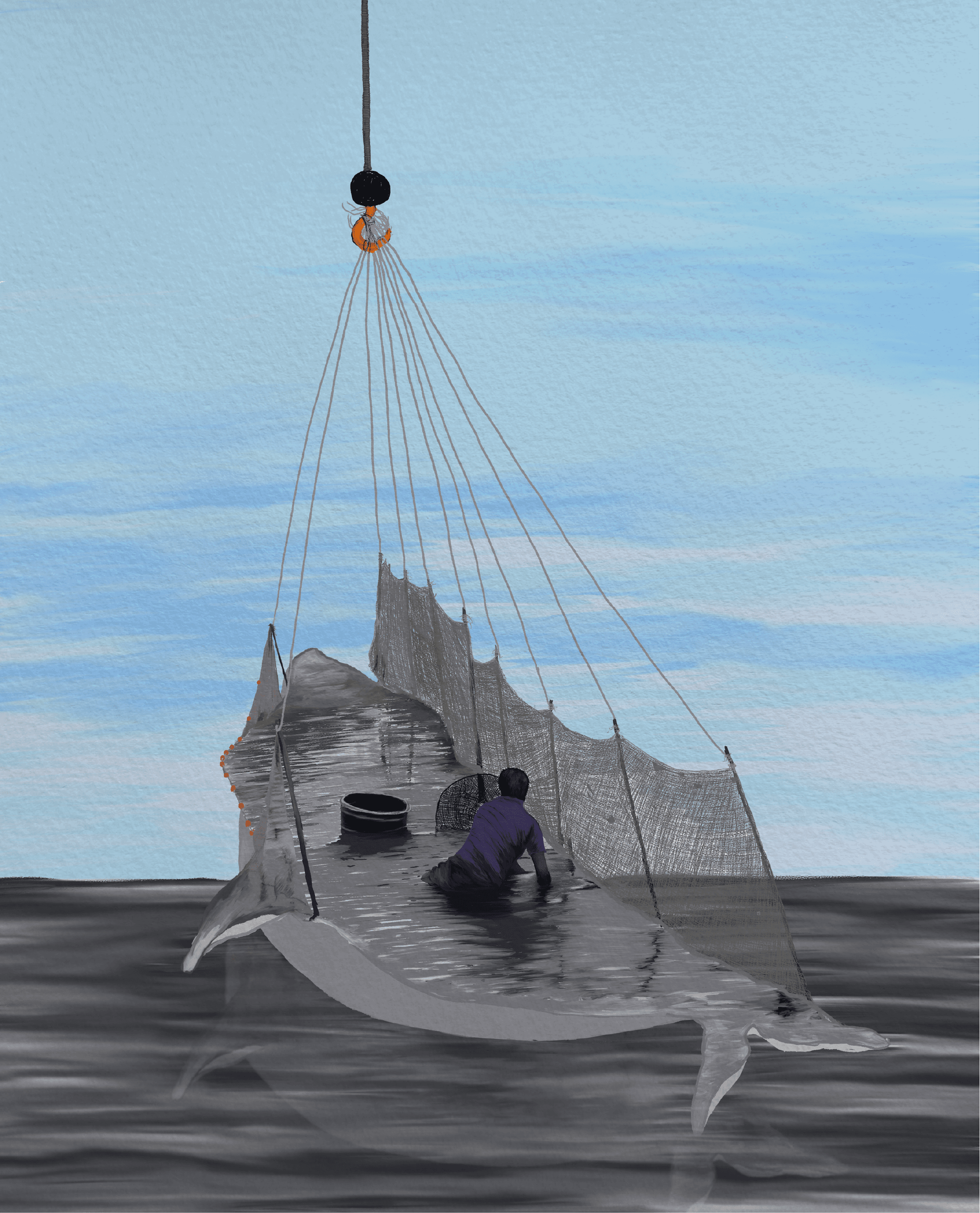

Fishing

Sinking Peripheries & Floating Labourers: Kochi’s Battle with Rising Seas

Elders of Chellanam recall a time when mangroves and sea plants bordered the shore and beaches, 2km wide. Today, those mangroves became ghosts, the beaches erased by rising seas, dredging and port expansions. “My grandmother married into a house that no longer exists,” says Jaison, an ex-fisherman of Manassery, near Chellanam. “By the time I was born, the ocean had claimed five homes.”

The coastal stretch from Fort Kochi in the north to Andhakaranazhi in the south spans 25 km, but much of it remains poorly protected. Besides the tetrapod project, dilapidated seawalls and groynes made of granite and sandbags are common sights. This is especially true in areas like Kannamaly, Saudi and Manassery, where some houses stand just 1 meter from the sea.

Ex-Fishermen / Ex-Chavittunadakam artists of Saudi

Paulson, once a fisherman, now ferries gas cylinders to repay the home loan for a home waiting to be washed away. “Fishermen may have less education,” he says, “but you shouldn't call what we say foolish; we speak from our experience”.

Chellanam’s 15,000 residents are predominantly Latin Christian fisherfolks (historically Fisher castes converts) with 8% SC and a few Kudumbi families. Chellanam reflects Kerala’s 59.5% eroded coastline. Post 2018 flood, the state offered Punargriham, a ‘rehabilitation’ of Rs. 10 lakhs to abandon homes within 50 meters of the tide, with which they can't even buy a decent land.

Star of the sea, Pray for us: Chellanam Kochi Janakeeya Vedhi protest march in 2023

The 7.36 km long tetrapod sea wall project became a reality in 2024 only after intense political pressure from Chellanam Kochi Janakeeya Veedhi (CKJV), supported by the church and non-mainstream political parties. Through protests, indefinite strikes and political work spanning years, CKJV have demanded comprehensive coastal protection measures including beach nourishment, construction of breakwaters, and the proper maintenance of the sea wall. And the protest continues. The government is yet to extend the sea wall to Kannamaly, Manassery and the adjacent coastal areas. However, some residents are skeptical about the long-term effectiveness of tetrapods. Continuous wave action may erode their surfaces, and questions remain about their ability to withstand cyclones and monsoons. For instance, cyclone Tauktae in 2021 caused severe inundation in Chellanam despite low rise, exposing the limitations of current protective measures like tetrapods.

Meanwhile, the Sagarmala project unfurls its blueprints: SEZs, logistics parks, a port-centric trade and security empire. However, such initiatives are part of a larger project of capitalist interests encroaching on coastal areas.

While Chellanam protests loudly, a quieter struggle unfolds daily in Edakochi, Kumbalangi, Puthenvelikkara, Ezhikkara and parts of Vypin. Here too, tidal flooding invades homes year-round, transforming streets into saline rivers and lives into endless cycles of repair. For the floating city workers and the children, walking to work means wading through debris-laced floodwaters.

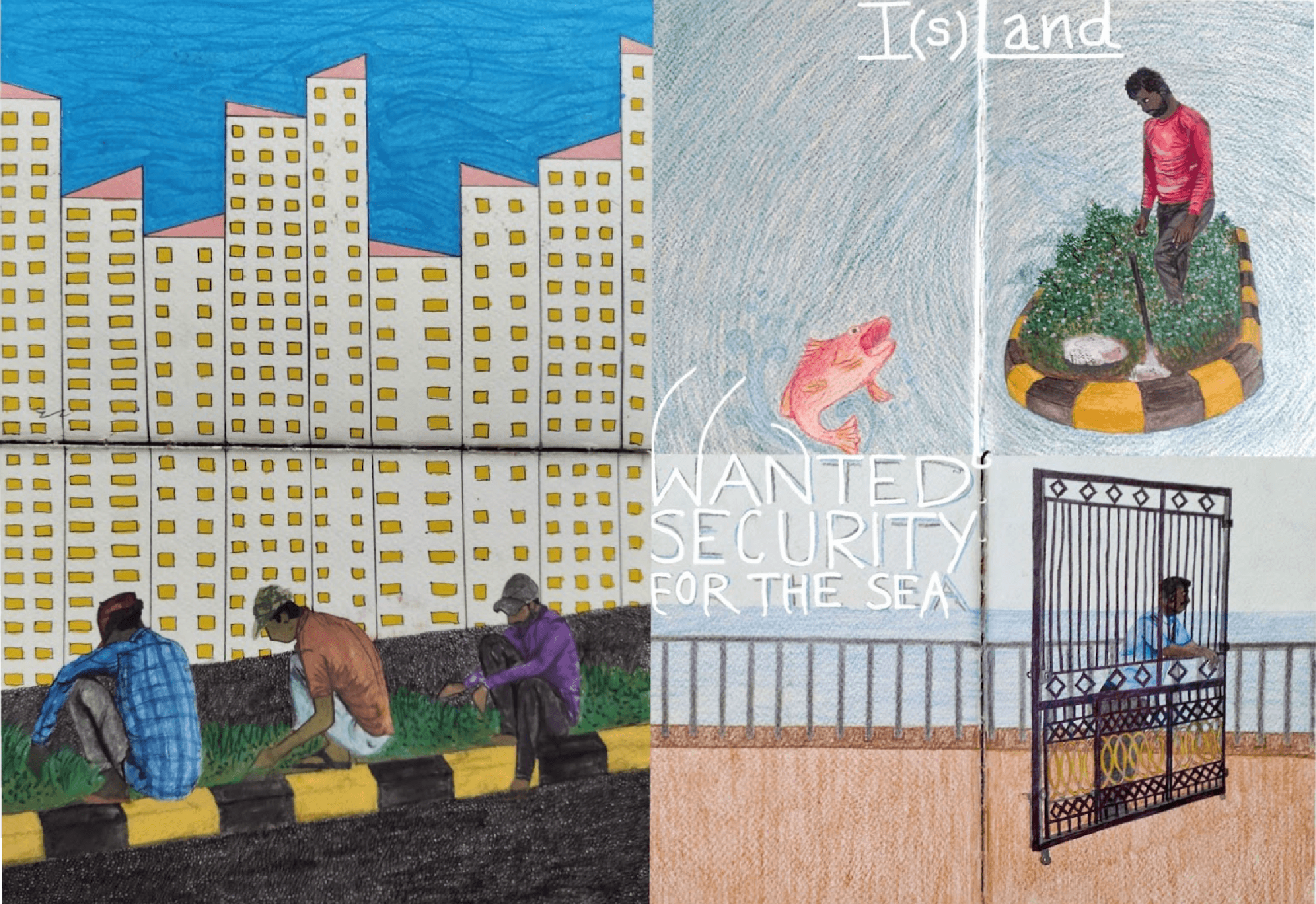

Food, Shelter, Cloth & Waste: Floating labourers

The city’s coastline has been vanishing at the rate of 0.158 cm/year in the period between 1987 and 2021, and the sea levels are projected to rise by 70mm by 2050. Tidal floods now persist for 8-10 months yearly, with high tides surging from 11 days (2011-2022) to 23 days in 2025. Slack tides last for hours, trapping seawater inland.

Salt intrusion corrodes wiring, crumbles walls, destroys furniture, causes skin conditions such as eczema, and poisons farmland. Tidal floods also sweep city garbage into homes. At least 300-400 houses in Puthenvelikkara are inundated everyday in a year. On Kumbalangi island, flooding happens twice a day. CRZ laws deny housing aid like LIFE scheme to those affected, trapping them in unlivable homes. The experts at Equinoct estimate tidal flooding has affected over 20,000 people across 23 grama panchayats. The state government, however, is yet to map the scale and intensity. Few collectives are mapping and studying the impact and protesting for state intervention.

Protest to construct temporary bunds at Edakochi, 2025

The working class, who sustain Kochi’s development, reside in these peripheries worst affected by climate change and urbanisation. Suburbs like Chellanam, Vypin, Edakochi and Paravur are home to many domestic and retail workers. These labourers flowing from the edges towards the centre and the east for livelihood, without access to the city’s benefits or involvement in its governance, are likely to be pushed off further from the city, with the rising sea level.

Where do they go, when the peripheries vanish?

Climate change, a never ending process akin to evolution, gains heightened awareness today due to rapid urbanization and our immediate experience of its effects. Moving beyond binaries like nature vs. humanity or climate change vs. urbanization is essential to grasp the entangled margins of caste, class, religion, gender, region, urbanisation and climate change. This entanglement manifests as social, spatial, and sensorial marginality, trapping vulnerable communities in ecologically precarious zones—the shrinking stenchy canals, sinking colonies, floodplains, and vanishing hill slopes and coastlines. For a city that emerged in the aftermath of the Periyar flood of the 14th century, now standing at the crossroads of urban development, dispossession, and climate crisis, the entangled margins become sites of neglect and disappearance.

Whose survival is planned for?

Who is built to float?

Who is left to sink?

¹ It excluded the plantation sector – most of the high land and a good part of midland. Harrisons Malayalam & Kannan Devan Hills plantation company holds a total of 49,000 hectares through lease. Then the local corporate groups and families (mostly Syrian Christians) and the Syrian Christian church remain the second and third mighty landholders in high land and midland.

Reform for garden land and rice fields was primarily a tenancy reform with transfer of land to intermediate and small tenants, which left out the majority of landless farmers. Now this land is mostly owned by upper caste Nairs and Syrian Christians, and to a much lesser extent, by Muslims and Ezhavas (OBC).

Also, the landlords circumvented reforms through family partition well ahead. The Congress led opposition party dominated by Nairs and Syrian Christians were opposing the reforms well back in 1957.

The Kerala Private Forest Act, 1971 enacted to bring private forests, particularly those held under ‘Janmam rights’ under government ownership and then assign them to landless farmers and agricultural labourers for cultivation. Not even 1% of the 23,000 hectares earmarked for redistribution are actually allotted. The Muthanga and Chengara land struggle demanded the same, but was met with brutal violence and strategies.

² The Aralam farm rehabilitation scheme stands as a stark example of policy failure, with nearly 2,000 Adivasi families forced to live in constant conflict with wildlife, as a result of flawed government approaches to resettlement and forest rights. The Adivasis and plantation workers (Dalits) of Idukki, Wayanad and Palakkad are the most affected districts.

Kochi does not reveal itself as a whole, but in fragments—an archipelago of margins where land, water, labour and capital meet. This visual essay is an attempt to piece together an understanding of Kochi’s urban transformation from an edge perspective. It is born from my PhD studying the urbanisation of Kochi.

When I began ethnography, I was in an exploratory mode, thrown into the field with all senses wide open. I walked alone and with others, and cycled to the junctions and edges, across the nook and corner of Kochi. Sometimes I took the bus, auto, metro and boat to experience other nodes of ‘in-between places’. Drawings and photography went parallel to writing. A visual narrative emerged as a dialogue between images and text with my flows across the shores of Arabian sea, Vembanad lake, rivers, canals, wetlands, rail and highways. Unintended, but organic!

The history of Kochi, from its origin as a natural harbor to its transformation into an engineered port city, reflects a complex interplay of geography, trade, migration, hybrid cultures, colonialism, technology, labour and capital. Ultimately, the evolution of Kochi is entwined with the flow of water, people, labour and capital. Kochi’s layered histories of settlement by Jews, Hindus, Christians and Muslims of different places of origin, caste, class and language have given rise to a diverse urban landscape often hailed as an abode of cosmopolitanism. Yet, beneath this romanticized narrative lies a more complex urban fabric, where coexistence is fragmented by gentrification and ghettoisation.

Unlike the centralized density of the mega cities of India, Kochi’s margins are dispersed across its coast, canals, islands, wetlands, and transport nodes, making marginalisation not just peripheral but archipelagic. These ‘rurban’ margins—where rural livelihoods, urban expansion, ecological vulnerability, and infrastructural neglect coalesce—are neither fully urban nor fully rural. They are marked by hybrid rhythms: rising sea level, tidal cycles, seasonal labour, partial infrastructure/service access, and intermittent governance. Kochi’s marginality is thus shaped by a distinctive coastal urban metabolism, where land, labour, capital and water converge to constantly reconfigure the conditions of survival.

Art is integral to sense-making; it doesn't just complement text, but invites different thinking. It becomes a critique—not just of urban form, but of urban knowledge itself. It becomes a method, a way of knowing, sensing, and thinking with the city, and of composing knowledge that is affective and grounded. This method reflects a politics of feeling, of sensing. It challenges the textual and technocratic dominance in knowledge-making and asserts the validity of felt experience as knowledge. More importantly, crafting consensus and solidarity requires more than just political will; it needs creative engagement that evokes the emotions, memories, hopes and dreams of citizens of the city.

Them: Love & Care amidst precarity and chaos of survival. Beside the Salem-Kochi highway, near Edappally, one a balloon seller, familiar presence near Ernakulathappan Ground and the other, a construction worker I once noticed resting at a bus shelter in Vathuruthy. The metro—a symbol of mobility and modernity—contrasts with the ocean, restless and unpredictable, revealing the coastal fragility beneath Kochi’s development narrative.

We will move through specific places in Kochi: P&T colony/apartment, Kammattipadam, Chellanam, Edakochi and the wider coastal belt—places that form interconnected nodes of archipelagic margins. This archipelago lives on the entangled forces of caste, class, religion, climate change, and urbanisation, where marginality unfolds in three entangled forms: social, spatial and sensorial.

Kochi city region

From P&T Colony to P&T Apartment: From Flood to Leak

“There we feared the water rising above our feet, now we fear the water from above,” Mini, a Dalit domestic worker and a resident of P&T apartment said with anger and anguish, about how their rehabilitation from colony to apartment turned into another cycle of disregard and neglect. Their old fear was the water below, the Perandoor canal relentlessly rising with tidal or rain water flood. Their new fear is the water from above, dripping through cracked ceilings and leaking toilets in the apartment that was meant to be their salvation.

P&T Colony – before and after demolition

Their story begins in the 1970s on Poramboke land on the shore of the Perandoor canal, behind the Ernakulam south railway station. Pushed to the margins of the city by debt, familial betrayal, and poverty, 80 families—Dalits, Ezhavas, a few Nairs and others—forged a community united by dispossession. Most of the women worked as domestics, men in precarious jobs. Despite its mixed caste composition, the label ‘colony’ branded all residents as Colonikkar—outcasts— morally distant and socially inferior.

Inside the P&T colony

Smitha, who lived in the colony till she married and moved away, remembers her childhood with a sense of shame. She describes being drenched in sweat at school after helping her mother with domestic work and the devastating moment a school friend cut her off because the friend’s father found out where she lived. Even Nair residents like Jagathamma lost nominal caste privilege, desperately insisting “I'm a Nair, dear”, as offered food was declined. A place like ‘colony’ becomes a caste-marker in itself, overriding other identities. Where you live determines who others believe you to be.

P&T Apartment: Leaks & Cracks

Life in the colony was an everyday battle against tidal or rainwater floods, infectious diseases, and the stench of the canal. Their rehabilitation to the new LIFE Mission-GCDA apartment, on January 26, 2024, was supposed to be the end to this undignified life. Instead, it brought new burdens: leaking roofs and toilets, cracked walls, a multi-story building without a lift, and disrupted access to city-centre jobs. The colony’s formation and stigmatization demonstrates how caste and class inseparably co-constitute urban marginality. People’s lives are subjects of state “experimentation”, devoid of agency and care.

P&T Colony & Kammattipadam along Perandoor canal

Kammattipadam: Rail-locked Pit of Flooded Ernakulam

Flooded KSRTC stand

Nestled behind the KSRTC stand, encircled by affluent neighbourhoods, near the Perandoor canal, lies the rail-locked Kammattipadam – a name derived from ‘kammatti’ grass that once thrived in its now concrete-filled paddy fields. Once fertile, the Pulaya (Dalit) and Kudumbi farmlands, which are now reduced to a triangular pit surrounded by rail, drown frequently in tidal and rain water. Aravindakshan, a resident of Kammattipadam, recalls childhood harvests with his grandmother, the landscape sustained by the life-giving Perandoor canal. This changed when the urban planners filled the paddy fields, destroying the existing drainage. The Kottayam-Ernakulam railway line severed the landscape, trapping tidal and rain water, neglecting drainage systems. “Every year,” Aravindakshan says “the railway increases its height, and we sink lower.”

Where is the water way?

Encroachment by both private and government entities, reckless dumping of plastic and construction waste, and the paving over of waterways to create roads and makeshift markets have drastically reduced the capacity of Kochi’s intricate network of canals. The Perandoor canal narrowed from 13m to 3m over 6km, becoming a stagnant polluted ditch.

Ditch: Between KSRTC stand & Rail

Today, 45 families—predominantly Dalits, with some Christian and Tamil migrants—live here. Electricity arrived only in 1991 via SC funds after relentless struggle. Trains blocking the sole access for more than one hour endanger lives during medical emergencies.

A Tamil migrant peanut seller living in Kammattipadam

“If Nairs and Namboodiris lived here, this problem would be solved in minutes,” says Aravindakshan. The caste dimension of neglect is inescapable; Dalit communities lack the political leverage and social capital to force action. Once a communist stronghold, years of party indifference have fractured community solidarity, pushing some towards Congress and the BJP in desperate search of justice and recognition.

Kammattipadam

The Paradox of the Kerala Model

There is no doubt that the modern Malayali identity—shaped by global trade, cross-cultural relations, socio-religious reforms, colonial administration, communist movements and the social democracy model—is putatively superior to that of other Indian states. Yet, beneath this narrative of progress lie deep-rooted hierarchies along the entangled lines of caste, class, religion, gender and region, that are further exacerbated and exposed by climate change and rapid urbanisation.

The 2018 floods uncovered the disproportionate impact on the marginalized: their losses, compounded by historical vulnerability and scarce resources, created wounds far deeper than those suffered by people who possessed the means to recover and rebuild their livelihoods. This inequality is built upon a foundation of incomplete social reforms.

Lottery, Liquor, Ration: Relief? A street dweller, a lottery seller at a flood relief camp, and a man outside a bar. For the marginalized, “relief” is too often reduced to charity, ration kits, or welfare handouts. Long standing demands—land redistribution for Dalits, autonomy for Adivasi communities, dignity in housing and labour—remain ignored. Even under a communist government, systemic justice gives way to token relief.

While the land reforms¹ of the 1970s addressed, even if partially, the class aspect of land question, it failed to address its caste and community aspects. The landless agricultural labourers, Dalits and Adivasis were relegated to flood-prone lands, colonies (3/5/10 cent plots) and remote, landslide/wildlife attack-prone highlands². Meanwhile, the corporates, dominant castes and elites continue to control the fertile garden land, wetland rice tracts and the plantations, with Adivasis and Dalits continuing to lose land through mortgage and fraud.

Tea over the hills: The Pettimudi landslide in the Western Ghats, Idukki, of 2020, destroyed 2 Layams (plantation workers colony) killing 66 people.

Centuries of caste-feudal domination and post-independent land reforms have entrenched the marginalisation of oppressed communities, while post-liberalisation policies like the SARFAESI Act and SEZ rules have accelerated land dispossession. Dalits and underprivileged OBC groups (including Latin Christians, Muslims, Dheevaras, and other Hindu communities) have been pushed into ecologically fragile and economically vulnerable zones. This pattern is starkly visible in coastal regions, where large-scale projects like the Cochin Port development and Vallarpadam Container Terminal have disrupted the traditional fishing and farming economies and undermined the very survival of coastal residents. In Kochi, areas such as Chellanam, Edakochi, Kumbalangi, Vypin, Ezhikkara and Puthenvelikkara stand on the frontline of vanishing land amidst unjust urbanization and intensifying climate change.

Fishing

Sinking Peripheries & Floating Labourers: Kochi’s Battle with Rising Seas

Elders of Chellanam recall a time when mangroves and sea plants bordered the shore and beaches, 2km wide. Today, those mangroves became ghosts, the beaches erased by rising seas, dredging and port expansions. “My grandmother married into a house that no longer exists,” says Jaison, an ex-fisherman of Manassery, near Chellanam. “By the time I was born, the ocean had claimed five homes.”

The coastal stretch from Fort Kochi in the north to Andhakaranazhi in the south spans 25 km, but much of it remains poorly protected. Besides the tetrapod project, dilapidated seawalls and groynes made of granite and sandbags are common sights. This is especially true in areas like Kannamaly, Saudi and Manassery, where some houses stand just 1 meter from the sea.

Ex-Fishermen / Ex-Chavittunadakam artists of Saudi

Paulson, once a fisherman, now ferries gas cylinders to repay the home loan for a home waiting to be washed away. “Fishermen may have less education,” he says, “but you shouldn't call what we say foolish; we speak from our experience”.

Chellanam’s 15,000 residents are predominantly Latin Christian fisherfolks (historically Fisher castes converts) with 8% SC and a few Kudumbi families. Chellanam reflects Kerala’s 59.5% eroded coastline. Post 2018 flood, the state offered Punargriham, a ‘rehabilitation’ of Rs. 10 lakhs to abandon homes within 50 meters of the tide, with which they can't even buy a decent land.

Star of the sea, Pray for us: Chellanam Kochi Janakeeya Vedhi protest march in 2023

The 7.36 km long tetrapod sea wall project became a reality in 2024 only after intense political pressure from Chellanam Kochi Janakeeya Veedhi (CKJV), supported by the church and non-mainstream political parties. Through protests, indefinite strikes and political work spanning years, CKJV have demanded comprehensive coastal protection measures including beach nourishment, construction of breakwaters, and the proper maintenance of the sea wall. And the protest continues. The government is yet to extend the sea wall to Kannamaly, Manassery and the adjacent coastal areas. However, some residents are skeptical about the long-term effectiveness of tetrapods. Continuous wave action may erode their surfaces, and questions remain about their ability to withstand cyclones and monsoons. For instance, cyclone Tauktae in 2021 caused severe inundation in Chellanam despite low rise, exposing the limitations of current protective measures like tetrapods.

Meanwhile, the Sagarmala project unfurls its blueprints: SEZs, logistics parks, a port-centric trade and security empire. However, such initiatives are part of a larger project of capitalist interests encroaching on coastal areas.

While Chellanam protests loudly, a quieter struggle unfolds daily in Edakochi, Kumbalangi, Puthenvelikkara, Ezhikkara and parts of Vypin. Here too, tidal flooding invades homes year-round, transforming streets into saline rivers and lives into endless cycles of repair. For the floating city workers and the children, walking to work means wading through debris-laced floodwaters.

Food, Shelter, Cloth & Waste: Floating labourers

The city’s coastline has been vanishing at the rate of 0.158 cm/year in the period between 1987 and 2021, and the sea levels are projected to rise by 70mm by 2050. Tidal floods now persist for 8-10 months yearly, with high tides surging from 11 days (2011-2022) to 23 days in 2025. Slack tides last for hours, trapping seawater inland.

Salt intrusion corrodes wiring, crumbles walls, destroys furniture, causes skin conditions such as eczema, and poisons farmland. Tidal floods also sweep city garbage into homes. At least 300-400 houses in Puthenvelikkara are inundated everyday in a year. On Kumbalangi island, flooding happens twice a day. CRZ laws deny housing aid like LIFE scheme to those affected, trapping them in unlivable homes. The experts at Equinoct estimate tidal flooding has affected over 20,000 people across 23 grama panchayats. The state government, however, is yet to map the scale and intensity. Few collectives are mapping and studying the impact and protesting for state intervention.

Protest to construct temporary bunds at Edakochi, 2025

The working class, who sustain Kochi’s development, reside in these peripheries worst affected by climate change and urbanisation. Suburbs like Chellanam, Vypin, Edakochi and Paravur are home to many domestic and retail workers. These labourers flowing from the edges towards the centre and the east for livelihood, without access to the city’s benefits or involvement in its governance, are likely to be pushed off further from the city, with the rising sea level.

Where do they go, when the peripheries vanish?

Climate change, a never ending process akin to evolution, gains heightened awareness today due to rapid urbanization and our immediate experience of its effects. Moving beyond binaries like nature vs. humanity or climate change vs. urbanization is essential to grasp the entangled margins of caste, class, religion, gender, region, urbanisation and climate change. This entanglement manifests as social, spatial, and sensorial marginality, trapping vulnerable communities in ecologically precarious zones—the shrinking stenchy canals, sinking colonies, floodplains, and vanishing hill slopes and coastlines. For a city that emerged in the aftermath of the Periyar flood of the 14th century, now standing at the crossroads of urban development, dispossession, and climate crisis, the entangled margins become sites of neglect and disappearance.

Whose survival is planned for?

Who is built to float?

Who is left to sink?

¹ It excluded the plantation sector – most of the high land and a good part of midland. Harrisons Malayalam & Kannan Devan Hills plantation company holds a total of 49,000 hectares through lease. Then the local corporate groups and families (mostly Syrian Christians) and the Syrian Christian church remain the second and third mighty landholders in high land and midland.

Reform for garden land and rice fields was primarily a tenancy reform with transfer of land to intermediate and small tenants, which left out the majority of landless farmers. Now this land is mostly owned by upper caste Nairs and Syrian Christians, and to a much lesser extent, by Muslims and Ezhavas (OBC).

Also, the landlords circumvented reforms through family partition well ahead. The Congress led opposition party dominated by Nairs and Syrian Christians were opposing the reforms well back in 1957.

The Kerala Private Forest Act, 1971 enacted to bring private forests, particularly those held under ‘Janmam rights’ under government ownership and then assign them to landless farmers and agricultural labourers for cultivation. Not even 1% of the 23,000 hectares earmarked for redistribution are actually allotted. The Muthanga and Chengara land struggle demanded the same, but was met with brutal violence and strategies.

² The Aralam farm rehabilitation scheme stands as a stark example of policy failure, with nearly 2,000 Adivasi families forced to live in constant conflict with wildlife, as a result of flawed government approaches to resettlement and forest rights. The Adivasis and plantation workers (Dalits) of Idukki, Wayanad and Palakkad are the most affected districts.

Kochi does not reveal itself as a whole, but in fragments—an archipelago of margins where land, water, labour and capital meet. This visual essay is an attempt to piece together an understanding of Kochi’s urban transformation from an edge perspective. It is born from my PhD studying the urbanisation of Kochi.

When I began ethnography, I was in an exploratory mode, thrown into the field with all senses wide open. I walked alone and with others, and cycled to the junctions and edges, across the nook and corner of Kochi. Sometimes I took the bus, auto, metro and boat to experience other nodes of ‘in-between places’. Drawings and photography went parallel to writing. A visual narrative emerged as a dialogue between images and text with my flows across the shores of Arabian sea, Vembanad lake, rivers, canals, wetlands, rail and highways. Unintended, but organic!

The history of Kochi, from its origin as a natural harbor to its transformation into an engineered port city, reflects a complex interplay of geography, trade, migration, hybrid cultures, colonialism, technology, labour and capital. Ultimately, the evolution of Kochi is entwined with the flow of water, people, labour and capital. Kochi’s layered histories of settlement by Jews, Hindus, Christians and Muslims of different places of origin, caste, class and language have given rise to a diverse urban landscape often hailed as an abode of cosmopolitanism. Yet, beneath this romanticized narrative lies a more complex urban fabric, where coexistence is fragmented by gentrification and ghettoisation.

Unlike the centralized density of the mega cities of India, Kochi’s margins are dispersed across its coast, canals, islands, wetlands, and transport nodes, making marginalisation not just peripheral but archipelagic. These ‘rurban’ margins—where rural livelihoods, urban expansion, ecological vulnerability, and infrastructural neglect coalesce—are neither fully urban nor fully rural. They are marked by hybrid rhythms: rising sea level, tidal cycles, seasonal labour, partial infrastructure/service access, and intermittent governance. Kochi’s marginality is thus shaped by a distinctive coastal urban metabolism, where land, labour, capital and water converge to constantly reconfigure the conditions of survival.

Art is integral to sense-making; it doesn't just complement text, but invites different thinking. It becomes a critique—not just of urban form, but of urban knowledge itself. It becomes a method, a way of knowing, sensing, and thinking with the city, and of composing knowledge that is affective and grounded. This method reflects a politics of feeling, of sensing. It challenges the textual and technocratic dominance in knowledge-making and asserts the validity of felt experience as knowledge. More importantly, crafting consensus and solidarity requires more than just political will; it needs creative engagement that evokes the emotions, memories, hopes and dreams of citizens of the city.

Them: Love & Care amidst precarity and chaos of survival. Beside the Salem-Kochi highway, near Edappally, one a balloon seller, familiar presence near Ernakulathappan Ground and the other, a construction worker I once noticed resting at a bus shelter in Vathuruthy. The metro—a symbol of mobility and modernity—contrasts with the ocean, restless and unpredictable, revealing the coastal fragility beneath Kochi’s development narrative.

We will move through specific places in Kochi: P&T colony/apartment, Kammattipadam, Chellanam, Edakochi and the wider coastal belt—places that form interconnected nodes of archipelagic margins. This archipelago lives on the entangled forces of caste, class, religion, climate change, and urbanisation, where marginality unfolds in three entangled forms: social, spatial and sensorial.

Kochi city region

From P&T Colony to P&T Apartment: From Flood to Leak

“There we feared the water rising above our feet, now we fear the water from above,” Mini, a Dalit domestic worker and a resident of P&T apartment said with anger and anguish, about how their rehabilitation from colony to apartment turned into another cycle of disregard and neglect. Their old fear was the water below, the Perandoor canal relentlessly rising with tidal or rain water flood. Their new fear is the water from above, dripping through cracked ceilings and leaking toilets in the apartment that was meant to be their salvation.

P&T Colony – before and after demolition

Their story begins in the 1970s on Poramboke land on the shore of the Perandoor canal, behind the Ernakulam south railway station. Pushed to the margins of the city by debt, familial betrayal, and poverty, 80 families—Dalits, Ezhavas, a few Nairs and others—forged a community united by dispossession. Most of the women worked as domestics, men in precarious jobs. Despite its mixed caste composition, the label ‘colony’ branded all residents as Colonikkar—outcasts— morally distant and socially inferior.

Inside the P&T colony

Smitha, who lived in the colony till she married and moved away, remembers her childhood with a sense of shame. She describes being drenched in sweat at school after helping her mother with domestic work and the devastating moment a school friend cut her off because the friend’s father found out where she lived. Even Nair residents like Jagathamma lost nominal caste privilege, desperately insisting “I'm a Nair, dear”, as offered food was declined. A place like ‘colony’ becomes a caste-marker in itself, overriding other identities. Where you live determines who others believe you to be.

P&T Apartment: Leaks & Cracks

Life in the colony was an everyday battle against tidal or rainwater floods, infectious diseases, and the stench of the canal. Their rehabilitation to the new LIFE Mission-GCDA apartment, on January 26, 2024, was supposed to be the end to this undignified life. Instead, it brought new burdens: leaking roofs and toilets, cracked walls, a multi-story building without a lift, and disrupted access to city-centre jobs. The colony’s formation and stigmatization demonstrates how caste and class inseparably co-constitute urban marginality. People’s lives are subjects of state “experimentation”, devoid of agency and care.

P&T Colony & Kammattipadam along Perandoor canal

Kammattipadam: Rail-locked Pit of Flooded Ernakulam

Flooded KSRTC stand

Nestled behind the KSRTC stand, encircled by affluent neighbourhoods, near the Perandoor canal, lies the rail-locked Kammattipadam – a name derived from ‘kammatti’ grass that once thrived in its now concrete-filled paddy fields. Once fertile, the Pulaya (Dalit) and Kudumbi farmlands, which are now reduced to a triangular pit surrounded by rail, drown frequently in tidal and rain water. Aravindakshan, a resident of Kammattipadam, recalls childhood harvests with his grandmother, the landscape sustained by the life-giving Perandoor canal. This changed when the urban planners filled the paddy fields, destroying the existing drainage. The Kottayam-Ernakulam railway line severed the landscape, trapping tidal and rain water, neglecting drainage systems. “Every year,” Aravindakshan says “the railway increases its height, and we sink lower.”

Where is the water way?

Encroachment by both private and government entities, reckless dumping of plastic and construction waste, and the paving over of waterways to create roads and makeshift markets have drastically reduced the capacity of Kochi’s intricate network of canals. The Perandoor canal narrowed from 13m to 3m over 6km, becoming a stagnant polluted ditch.

Ditch: Between KSRTC stand & Rail

Today, 45 families—predominantly Dalits, with some Christian and Tamil migrants—live here. Electricity arrived only in 1991 via SC funds after relentless struggle. Trains blocking the sole access for more than one hour endanger lives during medical emergencies.

A Tamil migrant peanut seller living in Kammattipadam

“If Nairs and Namboodiris lived here, this problem would be solved in minutes,” says Aravindakshan. The caste dimension of neglect is inescapable; Dalit communities lack the political leverage and social capital to force action. Once a communist stronghold, years of party indifference have fractured community solidarity, pushing some towards Congress and the BJP in desperate search of justice and recognition.

Kammattipadam

The Paradox of the Kerala Model

There is no doubt that the modern Malayali identity—shaped by global trade, cross-cultural relations, socio-religious reforms, colonial administration, communist movements and the social democracy model—is putatively superior to that of other Indian states. Yet, beneath this narrative of progress lie deep-rooted hierarchies along the entangled lines of caste, class, religion, gender and region, that are further exacerbated and exposed by climate change and rapid urbanisation.

The 2018 floods uncovered the disproportionate impact on the marginalized: their losses, compounded by historical vulnerability and scarce resources, created wounds far deeper than those suffered by people who possessed the means to recover and rebuild their livelihoods. This inequality is built upon a foundation of incomplete social reforms.

Lottery, Liquor, Ration: Relief? A street dweller, a lottery seller at a flood relief camp, and a man outside a bar. For the marginalized, “relief” is too often reduced to charity, ration kits, or welfare handouts. Long standing demands—land redistribution for Dalits, autonomy for Adivasi communities, dignity in housing and labour—remain ignored. Even under a communist government, systemic justice gives way to token relief.

While the land reforms¹ of the 1970s addressed, even if partially, the class aspect of land question, it failed to address its caste and community aspects. The landless agricultural labourers, Dalits and Adivasis were relegated to flood-prone lands, colonies (3/5/10 cent plots) and remote, landslide/wildlife attack-prone highlands². Meanwhile, the corporates, dominant castes and elites continue to control the fertile garden land, wetland rice tracts and the plantations, with Adivasis and Dalits continuing to lose land through mortgage and fraud.

Tea over the hills: The Pettimudi landslide in the Western Ghats, Idukki, of 2020, destroyed 2 Layams (plantation workers colony) killing 66 people.

Centuries of caste-feudal domination and post-independent land reforms have entrenched the marginalisation of oppressed communities, while post-liberalisation policies like the SARFAESI Act and SEZ rules have accelerated land dispossession. Dalits and underprivileged OBC groups (including Latin Christians, Muslims, Dheevaras, and other Hindu communities) have been pushed into ecologically fragile and economically vulnerable zones. This pattern is starkly visible in coastal regions, where large-scale projects like the Cochin Port development and Vallarpadam Container Terminal have disrupted the traditional fishing and farming economies and undermined the very survival of coastal residents. In Kochi, areas such as Chellanam, Edakochi, Kumbalangi, Vypin, Ezhikkara and Puthenvelikkara stand on the frontline of vanishing land amidst unjust urbanization and intensifying climate change.

Fishing

Sinking Peripheries & Floating Labourers: Kochi’s Battle with Rising Seas

Elders of Chellanam recall a time when mangroves and sea plants bordered the shore and beaches, 2km wide. Today, those mangroves became ghosts, the beaches erased by rising seas, dredging and port expansions. “My grandmother married into a house that no longer exists,” says Jaison, an ex-fisherman of Manassery, near Chellanam. “By the time I was born, the ocean had claimed five homes.”

The coastal stretch from Fort Kochi in the north to Andhakaranazhi in the south spans 25 km, but much of it remains poorly protected. Besides the tetrapod project, dilapidated seawalls and groynes made of granite and sandbags are common sights. This is especially true in areas like Kannamaly, Saudi and Manassery, where some houses stand just 1 meter from the sea.

Ex-Fishermen / Ex-Chavittunadakam artists of Saudi

Paulson, once a fisherman, now ferries gas cylinders to repay the home loan for a home waiting to be washed away. “Fishermen may have less education,” he says, “but you shouldn't call what we say foolish; we speak from our experience”.

Chellanam’s 15,000 residents are predominantly Latin Christian fisherfolks (historically Fisher castes converts) with 8% SC and a few Kudumbi families. Chellanam reflects Kerala’s 59.5% eroded coastline. Post 2018 flood, the state offered Punargriham, a ‘rehabilitation’ of Rs. 10 lakhs to abandon homes within 50 meters of the tide, with which they can't even buy a decent land.

Star of the sea, Pray for us: Chellanam Kochi Janakeeya Vedhi protest march in 2023

The 7.36 km long tetrapod sea wall project became a reality in 2024 only after intense political pressure from Chellanam Kochi Janakeeya Veedhi (CKJV), supported by the church and non-mainstream political parties. Through protests, indefinite strikes and political work spanning years, CKJV have demanded comprehensive coastal protection measures including beach nourishment, construction of breakwaters, and the proper maintenance of the sea wall. And the protest continues. The government is yet to extend the sea wall to Kannamaly, Manassery and the adjacent coastal areas. However, some residents are skeptical about the long-term effectiveness of tetrapods. Continuous wave action may erode their surfaces, and questions remain about their ability to withstand cyclones and monsoons. For instance, cyclone Tauktae in 2021 caused severe inundation in Chellanam despite low rise, exposing the limitations of current protective measures like tetrapods.

Meanwhile, the Sagarmala project unfurls its blueprints: SEZs, logistics parks, a port-centric trade and security empire. However, such initiatives are part of a larger project of capitalist interests encroaching on coastal areas.

While Chellanam protests loudly, a quieter struggle unfolds daily in Edakochi, Kumbalangi, Puthenvelikkara, Ezhikkara and parts of Vypin. Here too, tidal flooding invades homes year-round, transforming streets into saline rivers and lives into endless cycles of repair. For the floating city workers and the children, walking to work means wading through debris-laced floodwaters.

Food, Shelter, Cloth & Waste: Floating labourers

The city’s coastline has been vanishing at the rate of 0.158 cm/year in the period between 1987 and 2021, and the sea levels are projected to rise by 70mm by 2050. Tidal floods now persist for 8-10 months yearly, with high tides surging from 11 days (2011-2022) to 23 days in 2025. Slack tides last for hours, trapping seawater inland.

Salt intrusion corrodes wiring, crumbles walls, destroys furniture, causes skin conditions such as eczema, and poisons farmland. Tidal floods also sweep city garbage into homes. At least 300-400 houses in Puthenvelikkara are inundated everyday in a year. On Kumbalangi island, flooding happens twice a day. CRZ laws deny housing aid like LIFE scheme to those affected, trapping them in unlivable homes. The experts at Equinoct estimate tidal flooding has affected over 20,000 people across 23 grama panchayats. The state government, however, is yet to map the scale and intensity. Few collectives are mapping and studying the impact and protesting for state intervention.

Protest to construct temporary bunds at Edakochi, 2025

The working class, who sustain Kochi’s development, reside in these peripheries worst affected by climate change and urbanisation. Suburbs like Chellanam, Vypin, Edakochi and Paravur are home to many domestic and retail workers. These labourers flowing from the edges towards the centre and the east for livelihood, without access to the city’s benefits or involvement in its governance, are likely to be pushed off further from the city, with the rising sea level.

Where do they go, when the peripheries vanish?

Climate change, a never ending process akin to evolution, gains heightened awareness today due to rapid urbanization and our immediate experience of its effects. Moving beyond binaries like nature vs. humanity or climate change vs. urbanization is essential to grasp the entangled margins of caste, class, religion, gender, region, urbanisation and climate change. This entanglement manifests as social, spatial, and sensorial marginality, trapping vulnerable communities in ecologically precarious zones—the shrinking stenchy canals, sinking colonies, floodplains, and vanishing hill slopes and coastlines. For a city that emerged in the aftermath of the Periyar flood of the 14th century, now standing at the crossroads of urban development, dispossession, and climate crisis, the entangled margins become sites of neglect and disappearance.

Whose survival is planned for?

Who is built to float?

Who is left to sink?

¹ It excluded the plantation sector – most of the high land and a good part of midland. Harrisons Malayalam & Kannan Devan Hills plantation company holds a total of 49,000 hectares through lease. Then the local corporate groups and families (mostly Syrian Christians) and the Syrian Christian church remain the second and third mighty landholders in high land and midland.

Reform for garden land and rice fields was primarily a tenancy reform with transfer of land to intermediate and small tenants, which left out the majority of landless farmers. Now this land is mostly owned by upper caste Nairs and Syrian Christians, and to a much lesser extent, by Muslims and Ezhavas (OBC).

Also, the landlords circumvented reforms through family partition well ahead. The Congress led opposition party dominated by Nairs and Syrian Christians were opposing the reforms well back in 1957.

The Kerala Private Forest Act, 1971 enacted to bring private forests, particularly those held under ‘Janmam rights’ under government ownership and then assign them to landless farmers and agricultural labourers for cultivation. Not even 1% of the 23,000 hectares earmarked for redistribution are actually allotted. The Muthanga and Chengara land struggle demanded the same, but was met with brutal violence and strategies.

² The Aralam farm rehabilitation scheme stands as a stark example of policy failure, with nearly 2,000 Adivasi families forced to live in constant conflict with wildlife, as a result of flawed government approaches to resettlement and forest rights. The Adivasis and plantation workers (Dalits) of Idukki, Wayanad and Palakkad are the most affected districts.

Images by Abhinand Kishore